by Nicholas Ribush

First published in the Love Lawudo Newsletter

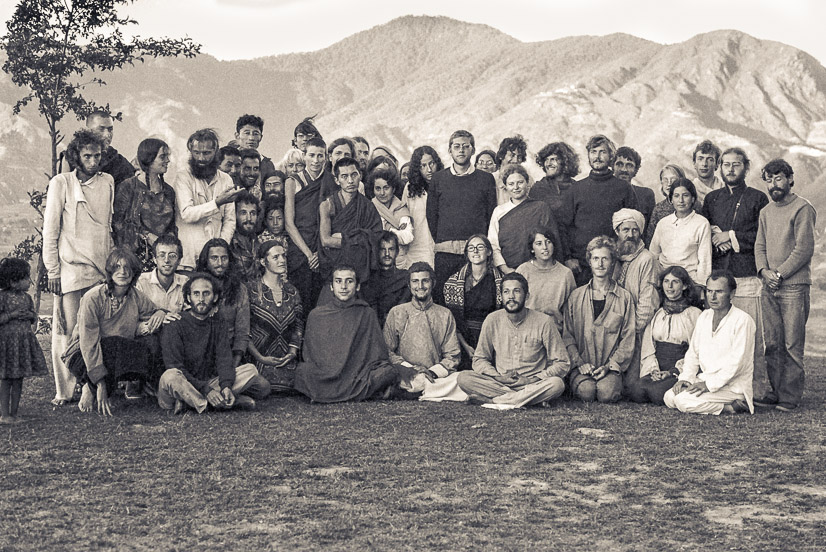

Kopan 1973

I first got to Kopan in October, 1972, just in time for the third Kopan meditation course.

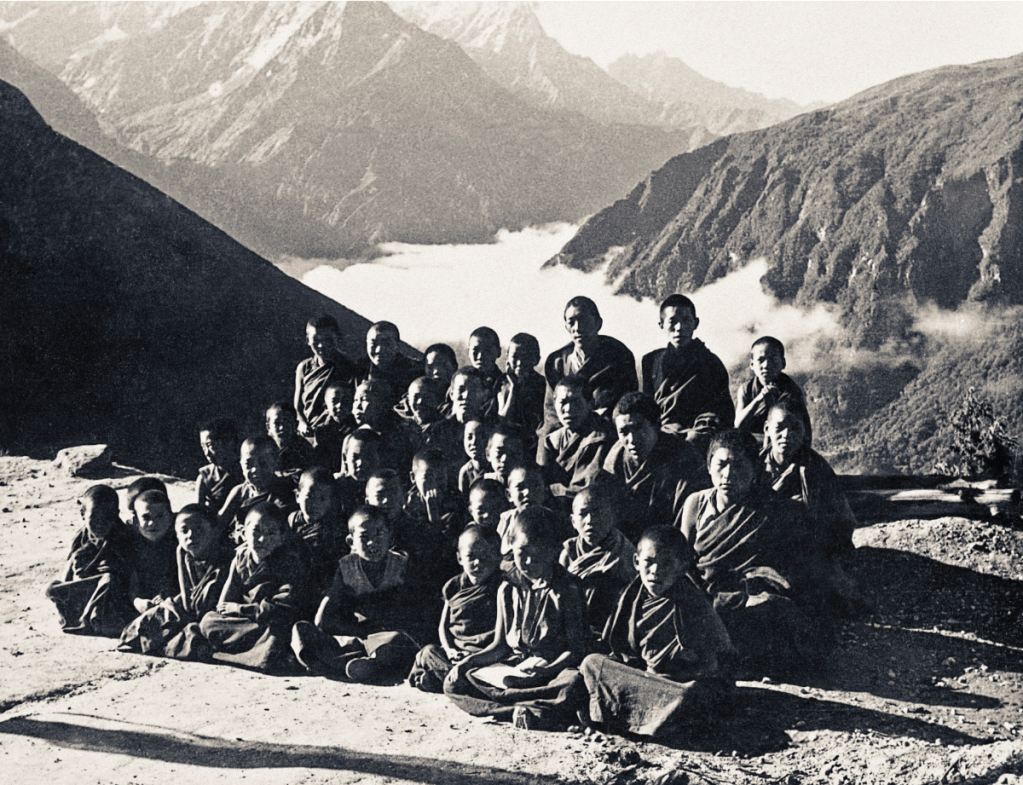

Some of those sitting in the front row include: Carol Corona, Massimo Corona, Nick Ribush, Claudio Cipullo, Steve (Malasky) Pearl, Piero Cerri, Lolly Smith, David Borrie, Darlene Darata, Age Delbanco (Babaji), Paula deWys. Some of those standing include: Ngawang Khedup (Ron Brooks), Chris Vautier, Losang Nyima, Losang Phagpa (the cook), Anila Ann McNeil, Lama Zopa Rinpoche, Jamyang Wangmo (Helly Pelaez, Jampa Chökyi), Shan Cooper, Luca Corona, Nicole Kedge (Couture), Ani Zamba (Suzanne Lee), Marcel Bertels, Dieter Gewissler, Barbara Vautier, Peter Kedge.

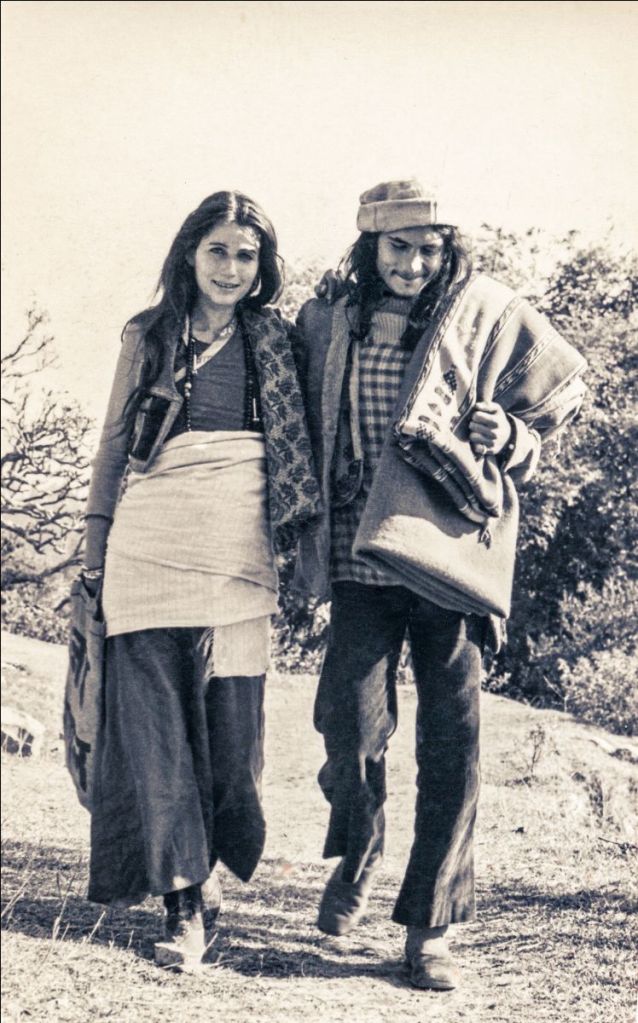

I knew practically nothing about Tibetan Buddhism when I arrived; by the end, I knew quite a bit more, but not enough, so I decided to stay on. I’ve told the story of why I was there before, so no need to repeat it here. After that course my girlfriend Marie, now Yeshe Khadro, and I worked with Lama Zopa Rinpoche to revise the course textbook, The Wishfulfilling Golden Sun, and prepare Kopan for the fourth course, to be held March-April, 1973.

By mid-April the main activity at Kopan had shifted to getting the approximately thirty monks to Lawudo for the summer. Lawudo in summer was a big deal for several reasons. First, the logistics themselves were a bit of a challenge. The small monks had to be flown up to the small town of Lukla, from where they’d walk. The older monks had to walk the whole way, which took the best part of two weeks. Much of the food for the five-month stay also had to be flown up: rice, dal, flour, powdered milk, sugar and so forth. What you could get up in Lawudo was pretty much limited to potatoes and tsampa.

Second, the visits of the Lawudo Lama were always highly anticipated events. Of course, if Lama Zopa Rinpoche’s mother and sister were to have their way, he would reside there permanently, and I always felt that they blamed Lama Yeshe a little for Rinpoche’s not being there year-round. I could understand their view, but they really had no idea of how beneficial Rinpoche was beyond the small pond of Lawudo rescuing sentient beings from the vast ocean of samsara. And that was just then. They had no idea of what was to come. None of us did.

For me, the big deal was that Marie (a nurse) and I (a doctor) were going up for the summer, too. Our plan was to take a couple of trunks of medicines up and set up a clinic in the Lawudo gompa to give the locals a few months of rudimentary medical treatment. We would also teach the boys English. So, while the monks busied themselves buying provisions and sewing them into sacks or filling countless old biscuit tins with flour and rice, we did our own food shopping and organized the many medicines that our many friends who came to the fourth course had brought from Australia and generally got ready for the exciting summer ahead.

This also meant paying farewell visits to those of our Australian friends who were still there. One day I went down to Kathmandu and dropped into the Thamel guesthouse where some of them were staying. Gil and Maz Richards were there, along with Dugald Sinclair and Steve Edwards. I found them bright yellow, sitting on their beds passing round a joint. They offered me a hit. I hesitated; these guys had hepatitis.

Attachment battled with logic and, as usual, won the debate. After all, I argued to myself, if they were yellow, it meant they were in the post-infection stage. They were suffering the ill effects of liver damage caused by the hepatitis-A virus, but the virus itself had gone from their systems. That was the theory. Also, these were my friends; they had come all this way at my behest. It was only right that I have a social smoke with them. Craving-desire, as Lama liked to call it, is really good at what it does. I took a few big hits, said goodbye and took off to the pharmacies on New Road, where I had set up deals with the pharmacists, whereby they let me exchange duplicate medicines for ones I didn’t have, as long as they finished ahead on the transaction.

Getting to Lukla

Around this time, Lama Yeshe returned from Thubten Chöling Monastery, near Junbesi, where he had gone to pay a visit to Zina Rachevsky (who had helped the Lamas find and establish Kopan and whose friends had helped fund the building of the Lawudo Gompa). Zina had been in retreat there for the past year or so. This would be the last time Lama would see her, as she died there a few months later. The older monks had already set off on foot and the food was packed, ready to go. The only remaining hurdle was getting everybody and everything to Lukla.

As readers of the Lawudo newsletter will know, Lukla is a small Sherpa village perched on the side of a mountain about nine thousand feet above sea level, overlooking the Dudh Kosi (Milk River, so-called because its ceaseless churning over rocks keeps it permanently white). From Lukla, it’s a two-day walk up to the town of Namche Bazaar, which lies at an altitude of twelve thousand feet above sea level. Namche is at the junction of two valleys. The one that goes northeast up to the right takes you to Thangboche Monastery, the famous monastery on the way to Everest base camp, and then on up to the big mountain itself. The Dudh Kosi courses through the one that runs northeast to the left. Lawudo is a few hours’ walk up this one and Thami, where Rinpoche was born, about an hour further on.

The plan, then, was for the young monks to fly to Lukla and walk up to Lawudo. Most of them came from the area between Namche and Thami and some planned to visit their families for a couple of days before going on to the monastery, which lay at fourteen thousand feet, some three thousand feet above the Dudh Kosi, a silver ribbon way below. Helly Pelaez, who, in the meantime, three days after Suzanne Lee, an English woman who was also an alumna of the third course, had been ordained in Dharamsala by Geshe Rabten as the nun, Jampa Chökyi (now Jamyang Wangmo), would fly up with the boys. Marie, Gareth Sparham, Dick Robinson and Merideth Hassan, who had gotten together after the course, would go a few days later. The Lamas, all the stuff and I would go last.

The plane you got to Lukla was either the Canadian-made, twin-engine Twin Otter, which held about sixteen people and needed relatively good weather, or the Swiss-made, single engine Pilatus Porter, which held about six and could handle slightly less ideal conditions. In those days, most of the pilots were Swiss. A look at the Lukla airstrip immediately made the term “short take-off and landing” graphically clear. It was a tiny sliver of lawn on the side of a huge mountain and seeing it from the air the first time could induce the thought, “Please turn around and go back to Kathmandu.” Of course, the best part of its being on the side of a mountain was that you could land uphill and take off down, which considerably reduced the runway’s need for length. A crumpled Pilatus by the side of the strip, which remained there most of the ’70s, didn’t do much to inspire confidence either. My insurance was to be flying with the Lamas.

Flying with the Lamas

The boys and the Injis gone, it remained for the Lamas, the food and me to go. Here was the other catch. At that time of year, you never knew if you’d get out or not. It depended on the weather, monsoon clouds were starting to gather, and if the mountain was swathed in fog, there was no way a plane could land. The bottom line was that the pilot should at least be able to see the sliver. However, the only way to find out if there’d be a flight was to go to the airport and wait for the weather report. Sometimes this came by radio, sometimes from other pilots returning after a successful trip, sometimes from other pilots returning from an unsuccessful trip, their little planes disgorging a grumbling group of disgruntled passengers. You took your chances; we took ours.

Since it was a lot closer to the airport than Kopan, we had stockpiled the provisions at Mummy Max’s old Rana mansion in Tinchuli. Early one late-May morning, Steve Malasky (Pearl), who usually drove the gray van the gompa had inherited from Ngawang Khedrub’s father, and I went down and loaded it up with the several hundred kilos’ worth of sacks and biscuit tins and headed for Tribhuvan. Mummy drove the Lamas direct from Kopan in her Jeep. We got to the airport and unloaded our mountain of stuff. We had two Pilatus Porters booked, one for the food, the other for whatever wouldn’t fit into the first, the Lamas and me. It did not look good. No planes had been able to go that day; Lukla was completely fogged in. But, you never knew; you had to wait. Lama knew, however. After an hour or so he decided we’d wait no longer and he, Rinpoche and Mummy went back to Kopan. Steve and I reloaded the van and took everything back to the mansion.

Talk about Groundhog Day. The following morning we replayed yesterday’s experience, with one notable exception. This time when it became clear that it was too cloudy to go, Lama decided that schlepping the stuff back and forth was a waste of energy and that we should leave it at the airport. As it was mainly my energy that was being wasted, I readily agreed, but then came the punch line. There was nowhere safe to store everything at the airport; someone would have to stay with it. That someone would be me. With that, they all turned around and left.

I surveyed the situation. There was a huge pile of food against the terminal wall and Nepalis everywhere, eager to get their hands on it. I wouldn’t be able to let it out of my sight. It was going to be a long twenty hours. I had one fallback. Before leaving Kopan, Harry Luke had kindly offered me his camera so that I could record the forthcoming adventure on film. At the last minute he handed me something else—a small piece of soft black hash. “Next full moon,” he said dreamily, “Sit out on the mountain, smoke this and think of me.” Stuff the full moon. This was an emergency. Anyway, there was enough to keep me entertained until the next day and still have some left over for full moon. As the crowd thinned and people got used to this strange white person sitting on the floor keeping an eye on this skandha of food, I was unobtrusively able to roll and smoke a joint or three as day moved into night and in the end, I was completely alone.

Bright and early the next day—a lot brighter and earlier than I felt—the Lamas and Mummy showed up again. This time we were in luck and able to go. Coolies loaded up first one plane, then the other and finally, the Lamas and I got in. We took off. I looked at Lama. He had this intense look of concentration on his face and his lips were moving silently faster than I’d ever seen. He was saying mantras, nineteen to the dozen. I relaxed. We were as good as there.

Sure enough, after an amazing flight along one valley, then another, huge mountains towering menacingly to either side, there it was, the Lukla strip. Despite Lama’s mantras, my heart was uncontrollably in my mouth. He’s not really going to touch down there? But he’d done it before and he did it again and we were on the ground. I recalled the words of an English boys’ magazine hero: “Ah, terra firma. The more firmer, the less terror.”

Trekking with the Lamas

Lukla. What a scene. There was that crumpled plane, of course, a few grotty Sherpa huts and a sea of eager porters, all vying furiously to carry impossibly heavy loads up sheer mountains in severely oxygen-depleted air for basically nothing. I felt more fortunate than ever. Now a Lama Yeshe that I hadn’t seen before appeared. This was the one who bartered. He was pointing at this Sherpa and that, yelling some kind of mixture of Hindi, Nepali and Tibetan that probably most of them couldn’t understand either, but miraculously, within about ten minutes, all our stuff was strapped to people’s backs or in those baskets they carried by headband, and, after the Lamas finished the tea that was offered them, we were off to Lawudo.

The Sherpas knew exactly where they were going, so they barreled on ahead, while we strolled leisurely along the path. And what a breathtakingly beautiful walk it was. The first day was basically along the flat, rhododendron-covered mountains rising steeply to either side, the swirling waters of the Dudh Khosi, first to one side, then, as we crossed one of the several small, rickety bridges that spanned it, to the other. Everywhere, sometimes on a huge boulder in the middle of the churning stream, were rocks of all sizes with the ubiquitous mantra carved into them: om mani padme hum.

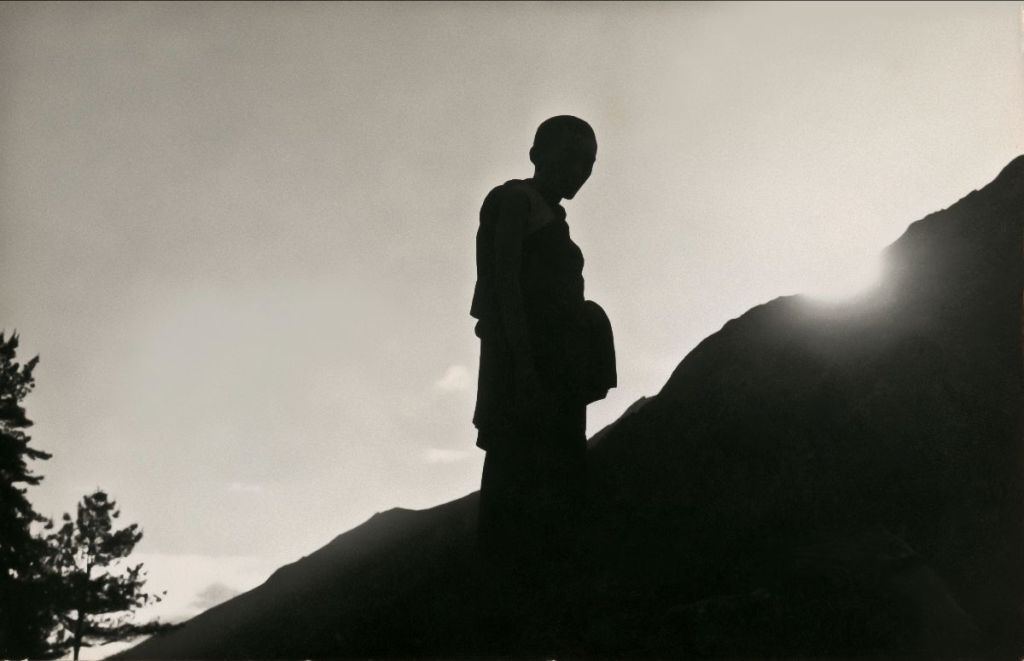

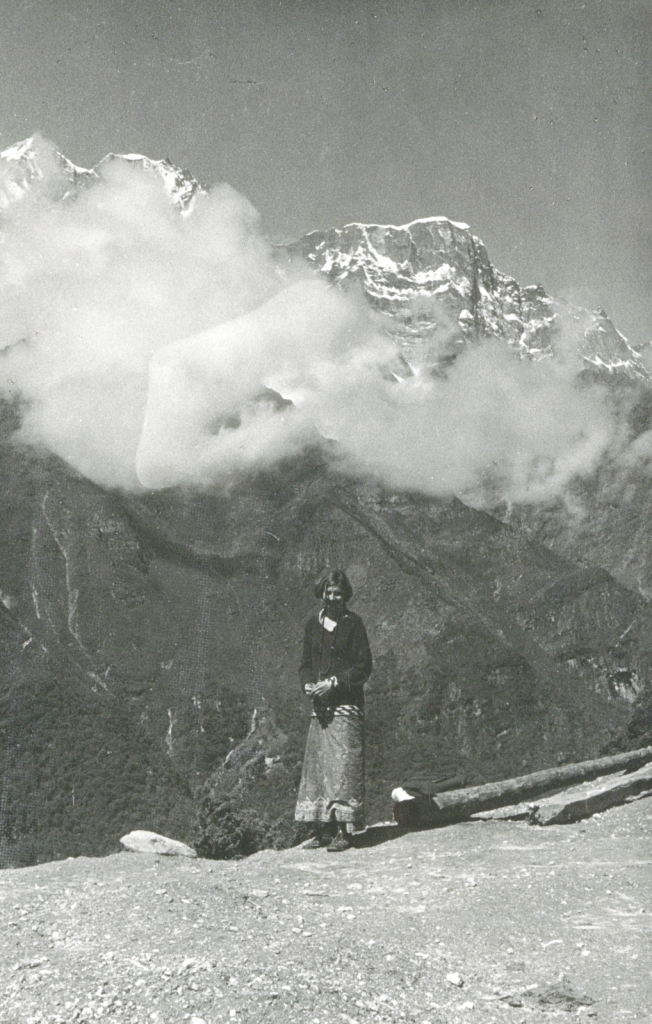

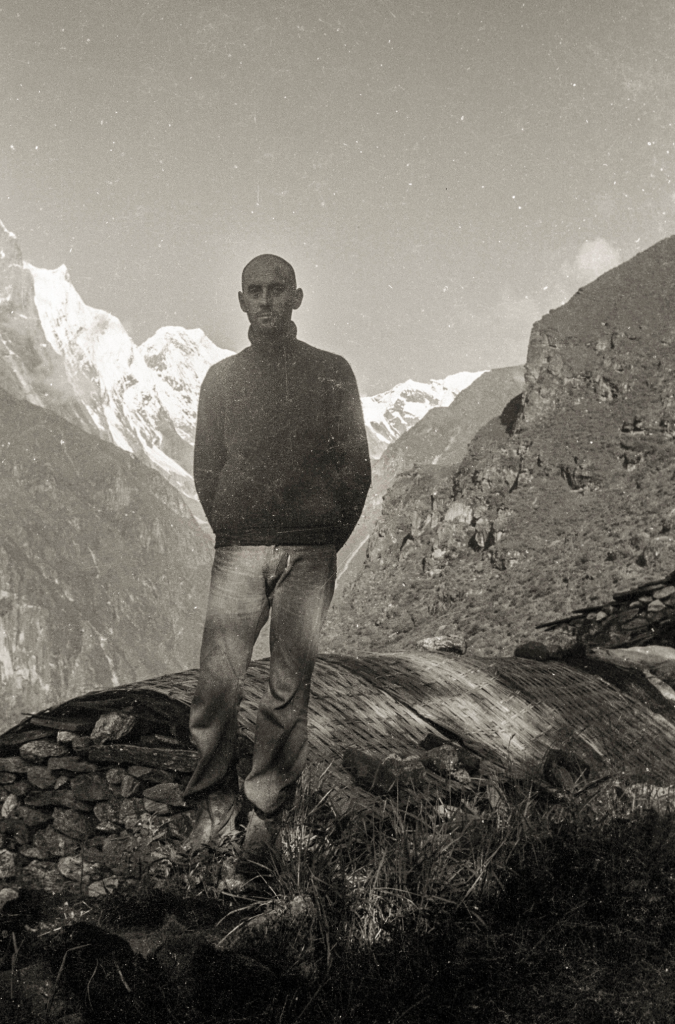

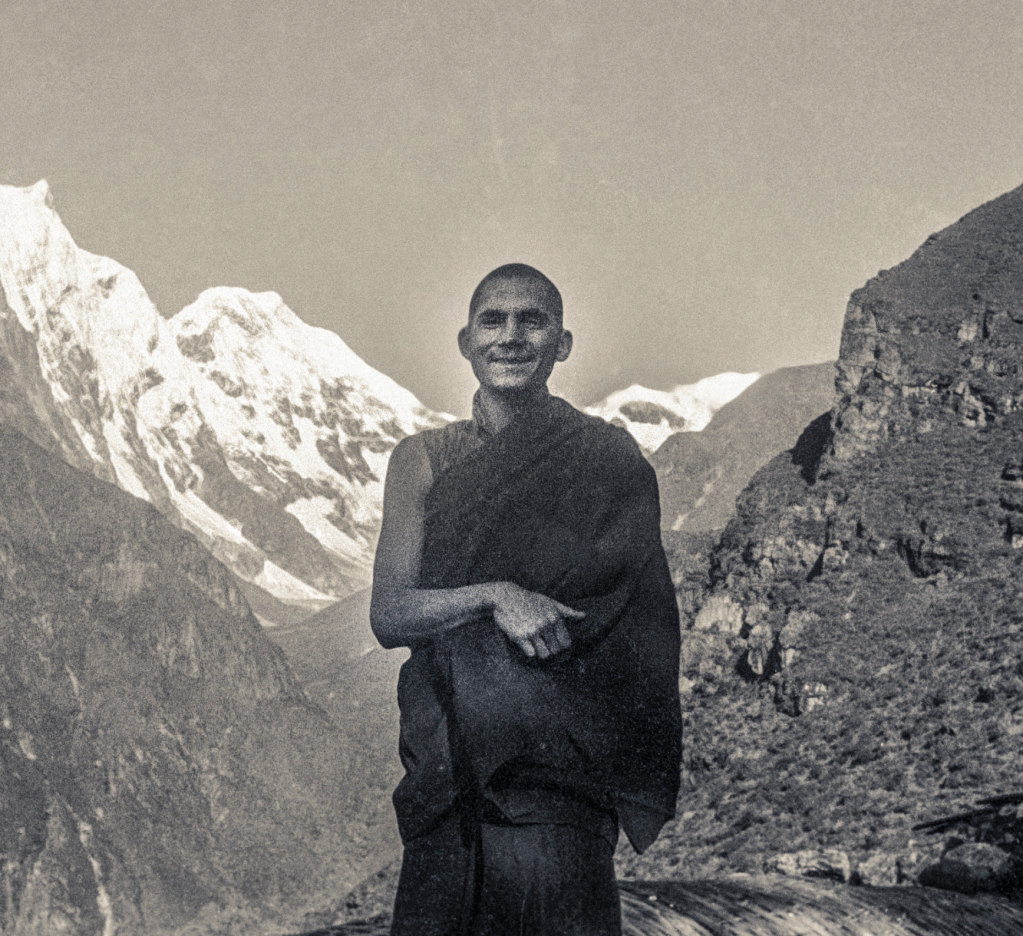

Lama Yeshe strode out briskly in front, Lama Zopa following a short distance behind, walking more slowly, meditatively, delicately, the same way he seemed to do everything. I tripped along happily just behind Rinpoche, stopping every now and then to put Harry’s camera through its paces, asking the Lamas to pause occasionally, on a bridge or beside a mani wall, while I snapped away. I savor the memory of that walk to this day. As simple as it was, it was a wonderful experience.

After a couple of hours, we stopped at a teashop for lunch and put away some pak, pronounced “puck” and to some, perhaps as tasty. I loved it. You put some tsampa in a bowl and slowly added delicious, buttery Tibetan tea, slowly working it with your fingers into the roast barley flour until it became stickier and stickier, then drier and drier until it formed a firm ball. My efforts at this in those days produced much merriment in the Lamas and probably still would. Tibetans are born into the art, if not the necessity, of making pak; Westerners rarely acquire the skill.

We continued on our way, sometimes catching up to our porters as they stopped for a smoke and a rest, passing them briefly, until they overtook us once more, racing along on their tight, wiry legs and huge, calloused bare feet, their splayed toes gripping the rocks like fingers as they sped over them until they were again out of sight.

An hour or so later, Rinpoche pointed out to me the cave of Gomchen Rinpoche, a well-known local meditator said to be the incarnation of the famous fifteenth century Tibetan scholar, poet, composer, doctor and saint, Tangtong Gyalpo, who invented iron bridges in Tibet. It was way up the mountain to the left, but all I could see were many multicolored prayer flags fluttering in the breeze.

By late afternoon we had reached a place called Monjo, where we would stay the night. The people there seemed to know the Lamas well, and Rinpoche especially was treated as a highly honored guest, although typically, he played it down as much as he could and always deferred to Lama. Being with them, I, too, received special treatment, which I tried to play down the way Rinpoche did, but it was like a monkey trying to imitate a human.

I had eaten with the Lamas many times before, and it was an oft-repeated scene, almost a game. First of all, Rinpoche was really thin and had what looked like an anorexic’s approach to food. The less he ate, the more he appeared to like it. This seemed to drive Lama to distraction, and he’d fuss over Rinpoche like a mother over an intransigent child. “Kusho, chö-na,” he would bark, insisting that Rinpoche eat. “Nos, nos,” Rinpoche would mutter in assent, pushing food about his plate and taking only an occasional bite. Rinpoche would also take ages to offer his food before eating; many a nice hot meal was well cold by the time Rinpoche started eating. Lama would never wait, of course, and would sometimes have finished his meal before Rinpoche had even started his, punctuating his mouthfuls with muffled exhortations for Rinpoche to eat. Ever the dutiful disciple, I, in the meantime, could never start before my guru, but while Rinpoche was creating skies of merit with his protracted offering, I was creating the cause for countless rebirths in the hells or as a preta by getting alternately irritated by the wait or overcome by greed.

We were up early the next morning to find that our porters had already left. The honor system amazed me. We had what to the Sherpas would have been a fortune in supplies but we barely had to keep an eye on them. I guess if you ripped anybody off even once, everybody knew who you were and you’d never work in that town again. They also probably knew a little about karma.

It was two hours to the beginning of the steep path that took you up two thousand feet into Namche, another beautiful walk. As we wound our way along the flat, I heard a bit of a commotion coming towards us up ahead but couldn’t see anything. Suddenly, over a rise, came a bunch of disheveled Sherpas, ruddy-faced, reeking of alcohol, laughing and falling about. As soon as they saw the Lawudo Lama they fell silent and, looking extremely sheepish, bowed their heads low to receive his blessing as they passed. Rinpoche gave each of them a perfunctory tap on the head and they continued quietly on their way. Noticing his apparent look of disdain, I asked him, piously, “Rinpoche, they’re supposed to be Buddhists. Why do they drink like that?” “Oh, it’s just craving,” Rinpoche replied, and moved off ahead of me once more.

I stopped for a moment, my hand automatically going to my breast pocket, where I’d secreted what was left of Harry’s hash after its airport experience. “It’s just craving,” I thought to myself, and in a flash of wisdom, I took it out and flung it into the bushes. A pang of regret later and I’d caught up with Lama and Rinpoche and we continued on as if nothing had happened. Actually, not much had, but I had this feeling that for a moment, perhaps, I’d practiced a bit of Dharma.

I should add that as well as a lump of hash, Harry Luke had kindly lent me his camera for the summer, so I was able to take lots of photos during this trip, some of which appear as part of this tale.

Note: all photos courtesy Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive

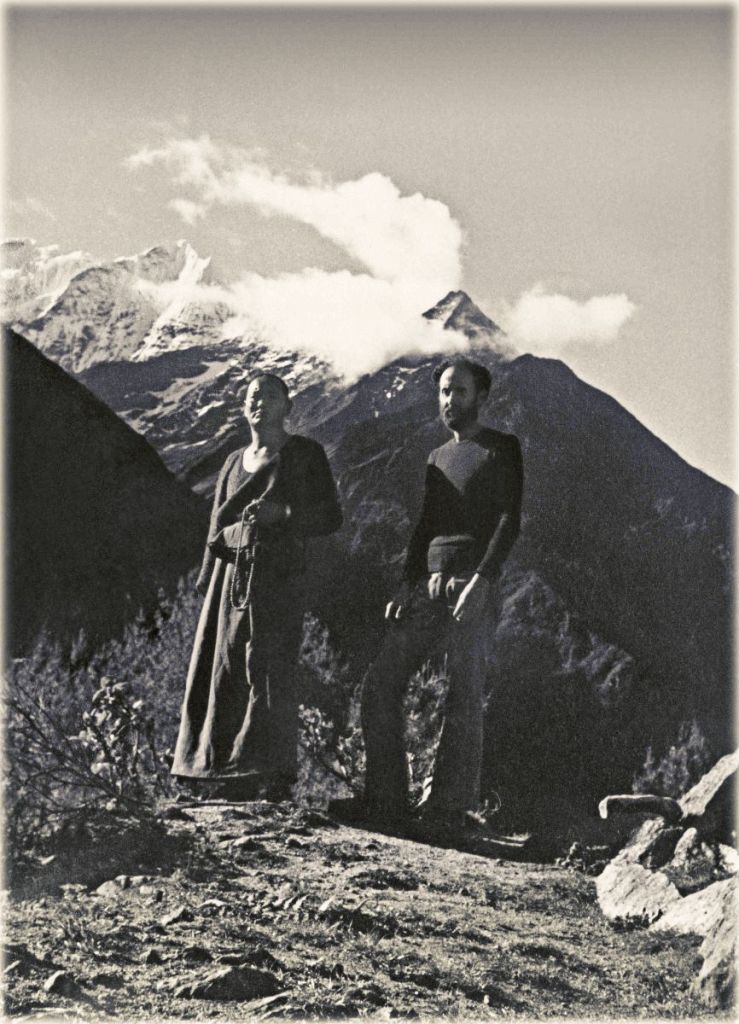

We climbed the steep hill to Namche Bazaar, stopping every now and then for Lama to take a rest. At one point, Lama said, “Zopa, you take photo Doctor and me.” Whenever he wanted me to know what he was telling Rinpoche he’d speak in English; oftentimes I think the message was actually for me. As I lined up the camera for Rinpoche, I saw that Lama had picked out the perfect shot. I stood to the side of the path with Lama, mala in hand, ceaselessly muttering mantras; behind us was a deep valley and beyond it, a couple of snow-covered peaks with wispy white clouds rising from them. Rinpoche took the picture and we moved on up the hill. Later, I sent the photo to my mother, writing, perhaps prophetically, “Lama Yeshe and son” on the back.

Namche Bazaar

We got to Namche mid-morning and went to a guesthouse owned by the parents of one of the Mt. Everest Centre monks. Lama sent the porters on to Lawudo with a note for Lama Lhundrup to pay them while we settled in for lunch. The plan had been to get to Lawudo, a few hours away, the same day, but it soon became clear that that was not going to happen. Too many people wanted to see the Lamas, especially the Lawudo Lama. This provided what appeared to me an interesting tension. Everywhere else in the world, Lama Yeshe was the teacher and Lama Zopa Rinpoche the disciple. And watching this closely over the years, as I did, was the best possible teaching on how to relate to your guru. Rinpoche’s devotion and demeanor were impeccable. Later, when I would study texts such as the Fifty Verses of Guru Devotion, I would see just how perfect a disciple Rinpoche was (and how far short I fell).

But to the Sherpas up here, the Lawudo Lama was the revered master and all attention focused on Rinpoche. As much as he tried to defer to Lama, Lama would withdraw and allow the spotlight to shine fully on Rinpoche. There’s a photo taken a few years previously by Georges Luneau, a friend of Zina, where the Lawudo Lama is sitting on a pile of rocks above Lama Yeshe. I can’t imagine the effort it must have taken to cajole Rinpoche to sit higher than Lama, but there it was. It was used on the cover of a French LP of Tibetan monks chanting that must have been one of the first such albums made. I’ve seen it recently on CD. It’s a wonderful photo.

Actually, I don’t really have to imagine the effort, because in later years, when I’d travel with the Lamas by train in India, we’d always travel in the two-tier air-conditioned car and Lama would invariably want the bottom bunk. I’ve seen Rinpoche try to travel sitting on the floor of the compartment because he didn’t want to sit above Lama’s head. In the end, however, Lama would always persuade him to climb up top, but it did take effort.

All day, people came to visit the Lamas and, in the afternoon, they accepted invitations to visit a couple of other families. I tagged along, of course, and again and again enjoyed the best food I’d eaten in months. Zen became a special favorite, a Sherpa dish made of cooked tsampa, swallowed in small pieces like an oyster, lubricated with a sauce made out of melted butter and some kind of pungent cheese that one Westerner described as smelling like a corpse. I also came to know and love the potato pancake.

Off to Lawudo

We stayed at the guesthouse that night and the next morning left for Lawudo. Even to walk the few hundred yards out of Namche took a while because people were lined up along the track to receive Rinpoche’s blessings, but we finally rounded the last corner and, losing sight of the town, saw our old friend, the Dudh Khosi, at the bottom of the valley to our left. We would more or less follow its course along the side of the valley for the next three hours until the path turned to the right to go down into the last valley, and there it was, high on the mountain opposite, the Lawudo Gompa. My first thought was, “Jeez, that’s a long way up,” but I nevertheless looked forward to the climb.

First, we had to go down to the bottom of the hill, which itself took about a half hour. We crossed a bridge over a small stream that ran in from a valley to the right and continued on to the Dudh Khosi and reached a fork in the path. Lama and Rinpoche had a brief conversation in Tibetan, the result of which was that Rinpoche and I would take the left fork and Lama would take the right fork alone. I didn’t know why we were splitting up like this, but of course, I just went along.

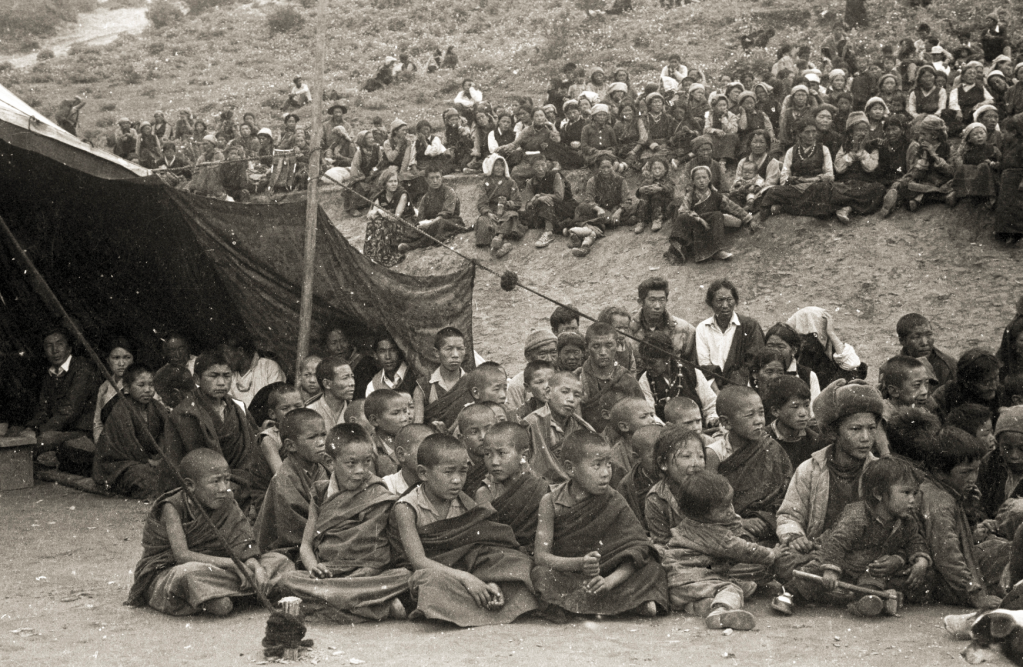

I tagged along behind Rinpoche, although he moved pretty fast. He was so light, the way he covered the ground and moved uphill, sometimes it seemed that he was floating. Our path took us first to the left, gradually up to the end of a spur that ran up to the right towards Mende, the little flat spot below Lawudo. It wasn’t a town or a village, just a couple of houses, a small stupa and a name. As we got to Mende, clouds of smoke started billowing up from in front of the Lawudo gompa. Branches of juniper were being burned as an offering of incense to the Lawudo Lama. As we drew closer I could see that there was a larger crowd than I would have imagined waiting for him. Not only were Rinpoche’s mother and sister, about thirty Mt. Everest Centre monks and the five Westerners there, but there were at least twenty Tibetan nuns as well. I asked Rinpoche who they were and he told me that they came from the Thamo (now Khari) gompa, which lay about halfway between Mende and the river below, but a bit to our right, towards Thangme, as I looked where Rinpoche was pointing. It had been established by a group of nuns who had escaped from Tibet in 1959 and they felt a close connection with Lawudo. Since the Lawudo gompa had been built, most years they would come up at Saka Dawa, the full moon of the fourth Tibetan month, the day when Guru Shakyamuni Buddha’s birth, enlightenment and passing away were commemorated, for a nyung nä retreat. Saka Dawa was a few days away and I was about to do my first nyung nä.

As we approached Lawudo, the crowd had spilled down along both sides of the path, nuns and monks bowed low to the ground thrusting forth khatags, white silk scarves, in a traditional Tibetan offering of greeting to Rinpoche. I hung back to stay out of the limelight and was swallowed by the crowd as everybody closed in behind Rinpoche as he passed. This gave me time to look around and see where I was.

Lawudo

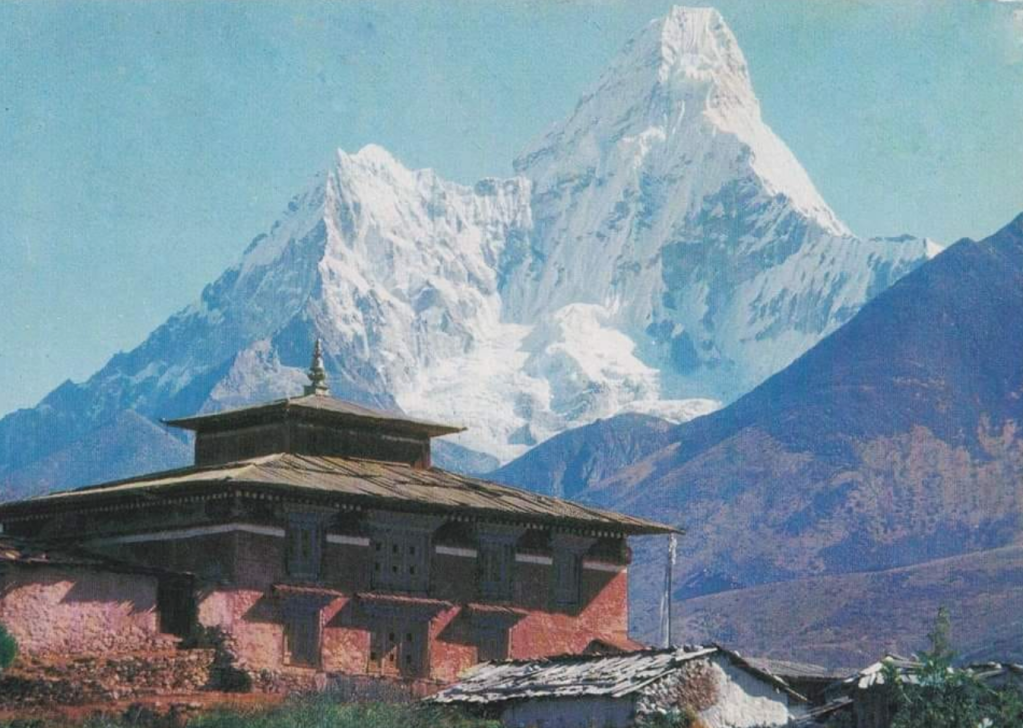

The two-story gompa, which was built in traditional style, looked unfinished. It was about one hundred feet across and perhaps fifty feet deep, set back on a little flat terrace carved out of the mountain. Off to my right, a wall made of large stones that didn’t fit together well shored up the front of the terrace. In the middle of the terrace was a tall prayer flag. Steps on either side led up to a small porch, which opened into the gompa. Most of the woodwork was still unpainted.

Rinpoche’s mother, sister and everyone else led him into the gompa, and as I came up to the terrace, I saw Marie—no, Yeshe Khadro, or YK, as everyone was now calling her—standing with the other Injis. I went over and greeted my mates, whom I hadn’t seen in all of a week, and asked if they’d seen Lama. They hadn’t. I thought that was odd, but maybe he’d taken his time getting there, as he had certainly chosen the much steeper, if shorter, route.

I went past the front of the gompa and up a path that led to some older buildings behind it. I saw now that you entered the upper floors of the gompa from the back. Nobody was around, so I went inside to take a look. One of the doors was ajar and as I peeped in I saw a pair of legs hanging over the side of a bed. I’d know those legs anywhere. They were Lama’s. “Lama,” I said, as I went in, “How did you get here?” He looked a bit tired, but smiled broadly and said simply, “I walk, dear.”

I still don’t know how he did it. This man with a bad heart had gotten up that really steep hill long before Rinpoche and I had—and we hadn’t dawdled—and into his room without being seen by anybody. It was weird. Thoughts of lung gom entered my mind, but it would have been of no use to ask Lama. He would never admit to supernormal powers. Perhaps, once again, he had simply not wanted to detract from the Lawudo Lama’s official greeting. Anyway, I was glad to see him there and went to find Lama Lhundrup to tell him that Lama was there and someone should look after him. I couldn’t do it; I didn’t know where anything was.

Lama Lhundrup was in the gompa. As I went down, I took in for the first time the spectacular view in front of me. The valley along which we’d come continued on to the right, the river boiling along it as usual, but down to the left, back towards Namche, the valley stretched long and deep, but it was full of cloud. A dense white fog, poetically described in Tibet as thick, fresh-made curd, crept up along the valley, getting ever nearer, but at an imperceptibly slow pace. By early afternoon we’d be completely shrouded in mist.

After I had fetched Lama Lhundrup from the gompa and followed him up to Lama’s room, I went back and looked out the second-floor door. Above me was an old building, the kitchen, with some store rooms to the left. To the right was a gate that opened into a small courtyard. I went up and had a look in. There it was, the Lawudo Lama’s cave. It wasn’t how I imagined a cave would look, like some sort of hole in the rock. It appeared that long ago, a piece of the mountain above had broken off and rolled downhill until it had wedged itself into the ground, with a significant overhang. Then some people had built a wall across the front, put in a floor, a door and a window and presto, a cave. I don’t know if that’s how it was in the Lawudo Lama’s previous life, but that’s how it was in this one. The woodwork was painted in bright reds, yellows and blues, and little frilled Tibetan curtains fluttered gently in the breeze. It was a magical sight, a hideaway from another time.

A low growl awoke me from my reverie. Just below the level of the cave I saw a large black Tibetan mastiff, thankfully chained, looking up at me, saliva dripping from his jaws. I said, “Good boy, om mani padme hum,” and walked slowly back down towards the gompa. He looked a lot like Gomchen, the Kopan mastiff, with whom I maintained friendly but reasonably formal acquaintance. With Gomchen, I never quite knew where I was, which I’m sure is how he liked it, and I suspected I would have the same kind of relationship with the Lawudo dog.

YK had been there for a couple of days and filled me in as to what was what. The medicines had come up with her and the others and were in another room in the gompa, a couple of doors from Lama’s. This is where the clinic would be. English would also be taught in there. But we weren’t staying in this room. We weren’t even staying at the gompa. We were staying in a house Rinpoche had in a place called Genupa, about fifteen minutes’ walk down (and twenty minutes back up) away from the gompa to the right, in the direction of Thangme. It was a small Sherpa house and all of us Injis were going to stay there.

However, before moving to our future accommodations, we would stay a few days at the gompa for the three days of the nyung nä, laying our sleeping bags on whichever piece of upstairs floor we could find. I chose the attic. The Saka Dawa nyung nä was a major event up here. The nuns came up from Thamo and lay people came from all over. All together there must have been one hundred people in the gompa.

A nyung nä works like this. The first day, you get up early and take the eight Mahayana precepts, much as we did for the last half of the Kopan course. There are four long retreat sessions each day, about two and a half hours each, during which you chant through the nyung nä sadhana, an extended Chenrezig practice that has you up on your feet doing many prostrations much of the time. The Thamo nuns clearly loved doing this and at times their chanting sounded like a choir of angels. Their enthusiasm was infectious, and I thought that probably the best place in the universe to be at Saka Dawa would be the Lawudo gompa doing nyung nä with the Lawudo Lama and the Thamo anis.

The second day you again get up early and take precepts, but this day you don’t eat or drink at all. You’re not even supposed to brush your teeth in case you accidentally ingest a drop of water. Here’s where you really see your mind. Attachment, craving, desire and greed all raise their heads and scream for attention. Rational ego arises and argues the stupidity, danger, lack of necessity and extreme nature of this practice. Anger, irritation, annoyance, frustration and impatience also surface regularly throughout the day, especially during the never-ending prostrations. It’s a great way to get to know yourself.

The third day you again wake up early to find that you’ve survived. At the first session, delicious, thick buttery tea is served, followed by an unbelievable rich and heavy breakfast of tsampa dough-balls. These are mini paks, soaked in butter and coated with sugar. After thirty-six hours of fasting, they taste pretty amazing. Then everybody goes home.

Enthronement

Well, normally everyone would go home, but this year there was a further order of business, the enthronement of Tenzin Norbu, one of the young monks from Namche. His ordination name was Thubten Zopa, the same as Lama Zopa’s (and mine, except that he, too, had Rinpoche at the end). The ceremony was a grand affair where he was led with great pomp and circumstance into the gompa and seated on a throne that was not quite as high as that of the Lawudo Lama, following which there were a couple of hours of prayers invoking the blessings of the buddhas for him to have a long life and be of benefit to all sentient beings. Then most everybody really went home.

Shik

However, when the Sherpas went, they left us a little legacy. Body lice. Although we’d had a little experience with head lice at Kopan, the Lawudo sojourn brought the reality home. Lice must have been a significant part of life in Tibet because references to lice are often found in Tibetan teachings. The thing is that in cold weather at high altitude you don’t wash all that often and tend to leave your clothes on for days at a time, at least the inner layers. This makes a nice warm permanent residence for body lice, which work their way deep into the seams of your clothes, where they lay their eggs, emerging only to drink your blood. The problem for a Buddhist is how to deal with these poor little sentient beings that, since beginningless time, have been our mother countless times each. You can’t kill them. Some people find it hard even to remove them from their home and throw them into the cold.

I remember one day, sitting on the Kopan gompa steps, removing lice from my hair and dropping them over the edge into the garden below. I didn’t feel completely good about this, but I was far from being one of those bodhisattvas who could offer his body to blood-drinking insects. There was a story about the young Lama Zopa Rinpoche at the refugee camp at Buxa, sitting on his bed naked from the waist up, offering his body to the mosquitoes. Sometimes, if I see a mosquito is already into me, I’ll let it fill up and leave, but I can’t go so far as to offer myself up. So, I picked off another louse and, dropping it over the edge, I looked down to see what sort of landing it would get. To my horror, which had to be hollow, I saw it land on a spider’s web and, as it did, the spider rushed out, grabbed it and took it back into its corner.

Up at Lawudo, lice cleaning had to be a serious undertaking. When you did it, you had to try to get rid of them all. That meant leaving clothes and sleeping bag out in the sun, when there was any—it was monsoon, and each morning the clouds came up the valley in that beautiful sight, enveloped the mountain, and stayed there most of the day—then turning everything inside out and assiduously going through it, seam by seam, gently removing any lice and placing them on the ground, trying not to think what would happen to them there. At that point, they were on their own. Then you boiled your clothes to try to get rid of any eggs, again assuming that they were just eggs and not sentient beings, but I really don’t know if that assumption was correct. At least, whenever we did any of this, we would pray for the welfare of the lice and all sentient beings. Shik was the Sherpa word for lice. It became a familiar term. You’d see someone itching and inquire, “Shik?”

Lawudo activity

The Lamas stuck around for another week or two, the Lawudo Lama in his cave receiving an endless stream of visitors, local Sherpas making offerings, seeking blessings and advice, and occasionally looking for a place in the monastery for their son. Lama Yeshe spent his time working with Lama Lhundrup to establish a teaching schedule for the monks and just being his wonderful, kind, funny, compassionate self with us Injis. During this time, Chris Kolb arrived to see Lama about getting ordained. He’d walked up via Thubten Chöling, where he’d spent a couple of days with Zina. He had wanted to see Trulshik Rinpoche, but he was at Tengboche.

Genupa

In the meantime, we set about moving into our new digs. The Genupa house was typical for the area. It was made of stone and had a thatch roof. There were two stories, the lower being where animals were usually kept, although there weren’t any when we were there. You entered through a low doorway and just to your right was a steep staircase, almost a ladder, leading up into the people’s living quarters. This brought you into the main room, which was very dark and had benches around the sides, radiating out from the focal point, the stove. It was made of stone and mud and stood only slightly higher than the benches to either side of it. The rafters were black with soot and the windows were small. A partition reaching two thirds of the way to the ceiling separated this room from a smaller area, which is where we decided the five of us would sleep, even though it meant there’d be only a foot or two between us. That would leave the main room free as a common area. Just off the main room to the right was a small door leading to the toilet, which was basically a hole in the floor. Whatever fell through would drop all the way to ground level, from where it would be cleaned out now and then, through an opening in the front wall of the house, which was sealed by a large rock. I never found out who did this particular job. We didn’t, and it wasn’t done while we were there.

The house was unusual in that there was a single-story addition off to the right of the toilet drop, a sort of storeroom, but it was not in good repair. Nevertheless, as a nun, Jampa Chökyi could not stay in mixed lay company, so she moved into it. However, a week later, Lama Zopa Rinpoche advised her to move up to the Charok cave, about fifteen minutes’ walk above the house, and Gareth, deciding that he didn’t like the intimate conditions in which he found himself, moved into the spare room Jampa Chökyi had just vacated. Early August, Jampa Chökyi had to leave to go back to Kathmandu because her visa had run out. Gareth moved up into the Charok cave, allowing Dick and Merideth, seeking the privacy that had long eluded the young lovers, to move into the spare room, leaving upstairs to YK and me.

As primitive and smoky as it was, I loved the Genupa house. Right next to it was a small spring, from which we could easily fetch fresh, clean mountain water and from the house, the view was fantastic. Way down below was the Dudh Khosi and across the valley were high, snow-capped mountains.

Note: most photos courtesy Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive.

The vegetation up and down the mountain was spindly scrub, punctuated here and there by a straggly pine, so that was nothing to write home about, but throughout the summer, flowers would grow everywhere in wild profusion, every couple of weeks a different crop, now white, now red, now yellow, now purple; it was beautiful.

Each day we would all head off up the hill to the gompa to fulfill our appointed tasks. About five minutes from the house we’d have to cross a forty-five degree, stony, fifty-foot-wide scar, the result of a landslide many years earlier that now blocked our path, lying like a static river of rocks of all sizes, to be negotiated carefully at least twice a day. Then it was a smooth, steady climb up a narrow path to the gompa, uneventful apart from the occasional yak or dzo blocking the path, always best given a wide berth.

Up at the gompa, Gareth and Merideth taught English, Dick was the handyman, and Marie (Yeshe Khadro) taught English, helped run the clinic and kept the young monks clean! Lama Lhundrup and the boys did their monk thing and everybody settled into a routine of sorts.

LP arrives

A few weeks later, there were three new arrivals. One was a tall, wiry monk with a mustache that reminded me of the one I’d seen in pictures of the Thirteenth Dalai Lama. In fact, the boys would later give him the nickname “Naro,” after the wavy line that was placed above Tibetan letters to make the vowel sound “o.” This was Lama Pasang Tsering, another of Lama Yeshe’s students from Sera, and, like Lama Lhundrup, he had come to help teach the monks and, more importantly, oversee the logistics of running the Mt. Everest Center (MEC). LP, as we immediately started calling him, was accompanied by a couple of young monks from Bhutan, who had also come to join the monastery.

Charok Lama

It wasn’t long before I got a first-hand look at another of Lama Pasang’s roles. I was sitting in the clinic one morning waiting to see if any patients were going to come that day when I heard raised voices in the classroom next door. LP was berating one of the monks for what, I didn’t know, but he was pretty exercised. It sounded like the youngster was talking back, because all of a sudden LP’s voice got louder and there was a loud swishing sound followed by a whack and a cry of pain. Several swishes and increasing cries later, I heard the classroom door open and a moment later a red-eyed little monk came into my room, tears running down his cheeks. It was Tenzin Dorje, another of the local boys, who, like Tenzin Norbu, was also an incarnate lama. He was also known as Charok Lama, being the incarnation of a monk called Ngawang Samten, who had meditated in the Charok cave for the last twenty years of his previous life and was much loved by the local community for all the nyung näs he used to do there, allowing them to join in whenever they wanted. It was said that every summer, he would see many yetis around the area. I never saw any.

The story was that Ngawang Samten’s mother had died and since he didn’t have the money to pay someone else to bury or cremate her, he carried her dead body up into the mountains to do it himself. By the time he reached the Charok area he was so exhausted that he dropped her and, being too weak to pick her up again, buried her right there. This experience caused him to generate strong renunciation and he decided to spend the rest of his life meditating in the Charok cave. This was where first Jampa Chökyi and then Gareth would spend part of the summer of 73, and in the summer of 74, I would return to retreat in it for four months myself.

Charok Lama was always rather shy, but this time I couldn’t get even one word out of him. He just turned his back and slipped his flimsy monk’s shirt off his shoulder, revealing several dotted welts down his back…LP had given him six of the best with his mala, which was, as I would discover over the years, the enforcer of choice for many a gekö, or disciplinarian monk. I was somewhat shocked by such a display of brutality from a Buddhist monk, but LP wouldn’t discuss it and I figured Tibetan monks had centuries of experience in managing monasteries and monks, so I’d better just leave them to it. As it happened, this was not a frequent occurrence, and Charok Lama must have really crossed whatever line he’d crossed. I reassured him and dabbed a little Mercurochrome on his wounds, and the little attention he received from me must have been enough, because he left the room smiling.

Eating

The staple foods up there were tsampa and potatoes. Lawudo spuds taste fantastic. I don’t know what it is, the type of potato, the soil they’re grown in, the fact that in the rarefied mountain air you get so hungry you’ll eat anything, but I loved them. Rinpoche’s sister, also called Ngawang Samten, used to boil up huge pots of little round potatoes until they reached that perfect stage where if you squeezed them gently in your fist, they’d pop up, skin-free, between your thumb and index finger. The squeeze was a bit of a skill, but one rapidly acquired. The naked spud was then dipped in a mixture of melted butter and salt and eaten whole. They grew all over the mountain and buckets of them filled the gompa kitchen.

Tsampa could be bought but could also be made. Gareth and I decided to try our hand. We collected together what we needed: barley grain, a sieve, a bucket of sand and a wok. Down outside the Genupa house we made a circle of rocks and inside it, built a fire. We loaded up the wok with sand and heated it over the flames. When the sand was good and hot, we removed the wok from the fire, threw a handful of barley into it and tossed it with the sand. It started popping immediately, like corn, and after ten seconds, we threw the mixture into the sieve and shook the sand out back into the wok. Lightly roasted barley, full of goodness, its natural ingredients not cooked out of it, remained in the sieve. We put it aside. We repeated this process for a couple of hours, handful by handful, until all the barley was cooked.

The next day, Gareth took it down to the mill at the bottom of the hill, where they ground it up for him. A couple of hours later we were eating our first batch of homemade tsampa. Delicious.

Gareth really got into tsampa. Up there you could get barley tsampa, of course, but there were also wheat, corn and millet tsampa, the latter being this strange-looking black stuff. He would mix a bit of this with a bit of that like some sort of mad Himalayan gourmet, constantly searching for the perfect-tasting combination. A couple of years later he wrote his first academic dissertation, a wonderful little paper entitled “Making Tsampa in Khumbu,” which, after lolling about for more than fifty years in total obscurity, I have now placed online for all to see.

Ngawang Chötak

Mid-June, Chris Kolb showed up again, in robes, having just been ordained at Tengboche by Trulshik Rinpoche.

He was now called Ngawang Chötak and planned to do retreat in a little cave above the Charok cave, where several years previously Lama Zopa Rinpoche’s uncle had done hundreds of thousands of prostrations to overcome a serious illness. The cave itself was too small for prostrations; you couldn’t even sleep lying down and had to spend the night sitting up in your meditation box. So Ashang (Uncle) Yönten spent seven years doing his prostrations on the flat rock outside the door facing his altar within. During this period he also took care of his blind mother.

Hepatitis retreat at Genupa

We’d been up there for over a month when I started to feel nauseous and unwell. I thought maybe I was getting the flu or something and took a couple of days off, staying home at Genupa reading one of the books I had brought with me, Conze’s Perfection of Wisdom in Eight Thousand Lines translation. Days passed, and although I spent most of my time in bed, I didn’t get better. In fact, I got worse; more nauseous and increasingly irritable. What really drove me nuts was the smoke from our fire. As in most Sherpa houses, the chimney worked extremely poorly if at all, so every time we made a fire, which was at least twice a day, the house filled with smoke and my mind with anger. It was this symptom that finally tipped me off to the potential diagnosis. I cast my mind back and calculated how long it had been since that fateful joint with Gil and the rest of my yellow friends back in Kathmandu (see part 1 of this story). It was a textbook six weeks, the classical incubation period for hepatitis A.

I knew there was nothing I could do but rest, avoid fat and try to eat as well as I could. Also, I should try to avoid infecting anybody else, so I had to keep my crockery and cutlery separate from that of the others. But what about the smoke? The worst thing was how mad I was getting; perhaps if I could control the smoke, I could control my mind. Poor Marie. She had to look after this angry little man. I couldn’t forbid everyone from lighting the fire, so I had Marie climbing all over the grubby partition, itself sticky with soot and tar from countless years’ smoke, tacking up our silver space blankets in an attempt to seal our room off from the main room. It helped a bit, but for the next week or so, every time the fire burned, so did I.

Then, one morning, I noticed that I seemed to be peeing tea. My urine was dark brown. I looked in the mirror. Sure enough, the whites of my eyes weren’t—they were yellow. I now knew that the recovery phase had started and that all being well, I’d be back to normal in a month or so. The knowledge itself made me feel much better, and, knowing that I’d still have to stay home while I recuperated, I made a plan to spend that time as constructively as possible.

I had brought with me my notes from the two Kopan courses I’d done, the third and the fourth, plus Brian Beresford’s notes from the latter. My intention had been to edit them into one whole to create a written commentary to Lama Zopa Rinpoche’s Wish-Fulfilling Golden Sun.

I set myself up at a low desk by the bedroom window and got to work. There was no typewriter and anyway, as it was, I couldn’t type, so I did the work by hand. I started off with Rinpoche’s introductory talks to each of the courses and then started cross-referencing his teachings with the pages of the textbook. It was painstaking work but I really enjoyed it and worked every day for as long as there was daylight.

After a week or so, I reached the part where Rinpoche was giving teachings on the perfect human rebirth, a human rebirth qualified by eighteen attributes that give us every opportunity to practice Dharma to the full. There were eight freedoms, freedom from the eight states that made it difficult if not impossible for us to practice Dharma, and ten richnesses, which endowed a person with all the conditions necessary to be able to practice perfectly. In working on these, I noticed that according to Rinpoche, the main advantage of the second, third and fourth richnesses was that they allowed one to be ordained as a monk or nun. When I thought about them, I could see that I was endowed with all three.

The first of the three was being in the center of a religious country. There are different ways of defining a religious country, but the one that was pertinent was that where the lineage of the pratimoksha ordination still existed. I had that. The second was being bodily intact, such that one was not disqualified from taking ordination. I had that, too. The third was not having created any of the five immediate negativities that would also disqualify one from ordination. Bingo! I hadn’t done any of those. Then it occurred to me that if I had these three richnesses, their main benefit being that I could take ordination as a monk, shouldn’t I take full advantage of this rare opportunity? Whoa—that was a scary thought.

I remembered after the fourth course that Chris Kolb had told his pregnant wife Lise Lotte that he wanted to become a monk. It came as a bit of a shock to her. Marie wasn’t pregnant; we weren’t even married. But what would she think? How would my mother take the news? I thought I’d better give this a bit more consideration.

Over the next few days I worked on a list of pros and cons. The list of pros kept growing but I was hard pressed to think of even one con that wasn’t totally bogus. I couldn’t find one reason not to become a monk. At the same time, I received a sign.

One day I was quietly working away on Rinpoche’s lamrim commentary when there came a knock at the door. I opened it to see a friendly looking Tibetan man—well, I’d already found that most of them looked friendly—and I invited him in. He was carrying a large bundle of clothes that he unwrapped before me. They were robes. He said that they were from Tibet and had belonged to a Thamo nun who had died recently and her relatives had asked him to sell them. He wanted a thousand rupees, which seemed a lot. Made of yak wool, they were very heavy. I could feel the quality. They were also in excellent condition. Everything in me said to buy them but still, I hesitated. Did I really want to take this step? What step? I wasn’t getting ordained; I was just buying a set of robes. If I decided to become a monk, I’d have my robes…well, I’d have my winter robes. You couldn’t wear these through an Indian summer. If I decided not to, I knew I could make a profit selling them at Boudha. I paid up.

He was very grateful. He pulled out from inside his chuba a large silver gau imprinted with the eight auspicious symbols. A gau is a sort of portable shrine that you wear on your belt or, if it’s a small enough, around your neck, when traveling. Inside it there might be a Buddha statue, mantras, sacred relics or other objects of spiritual significance. This one contained, wrapped in a faded piece of tattered red cloth, a statue of the Buddha with his face a bit squashed in. The man told me that on his way out of Tibet he’d been stopped by Chinese soldiers who searched everything he had. When they opened his gau and found this statue they hurled it to the ground. That was how it had gotten damaged. As precious as it was to him, he wanted to give it to me as a gift.

He also pulled out a strange looking piece of rock and told me to hold it in my fist. It fit absolutely perfectly, as if it had been molded to my hand. He said that this had once been an ordinary rock but a highly realized yogi had squeezed it like a piece of tsampa and pressed it into its present shape. He gave me that as well, and left.

That evening, Marie came home from the gompa. “How was your day?” I asked. Hers had been fine. “How was yours?” “Pretty good. I bought some robes.” “You what?” Shades of Lise Lotte. “I bought some robes.” I told her the story and the several days’ reasoning behind it. I’m not sure that she was convinced, but there it was. The man had gone away with the money, so there was no going back.

Soon after this I was well enough to start going back to the gompa to help with the clinic, but Marie was managing perfectly well without me and I was really into editing the course notes and wanted to finish before we had to go back down, so I finished up spending more time at Genupa than Lawudo. The more I worked on Rinpoche’s teachings, the more precious I felt them to be and the sadder I felt that we had missed so much. I knew from the two courses I had attended how much more he had taught than we had been able to capture and wondered how to overcome this problem. There was no electricity at Kopan and anyway, we didn’t have a tape recorder. There was no budget to buy one, along with tapes and batteries, but I thought of a solution.

His Holiness’ birthday

Each year, His Holiness the Dalai Lama’s birthday is celebrated on July 6. This year, 1973, it fell on a Friday, so up here the big celebration was to be on the 7th, at the weekly Saturday market at Namche Bazaar. Accordingly, early that morning, all the Mt. Everest Centre monks and we Injis headed off to Namche for the appropriate festivities: pujas, lama dancing, singing of songs and, of course, the selling of goods. The event lasted all day and it was dark by the time we got back to Lawudo.

This and that

In the meantime, I’d kept on reading the Perfection of Wisdom and it was blowing me away. I’m not sure why it affected me so strongly at the time; I read it again recently and it wasn’t quite the same. Back then, everything was so new and exciting; we were embarked on a wonderful journey of discovery. Of course, in many ways the book is basically incomprehensible, but the way it got to me was beyond the words.

By the middle of August, Jampa Chökyi had gone and Gareth was in the cave. One day he came down for a visit. I rushed out to see him, shouting excitedly, “Gareth! Gareth! The dharmas are empty!” I was joking around but he looked at me as if I were nuts. I told him about the book and lent him my copy. I also told him I’d been thinking about ordination. Now he looked at me as if I were really nuts. Nevertheless, as he told me later, both the book and my thoughts of ordination were to impact his life in a big way.

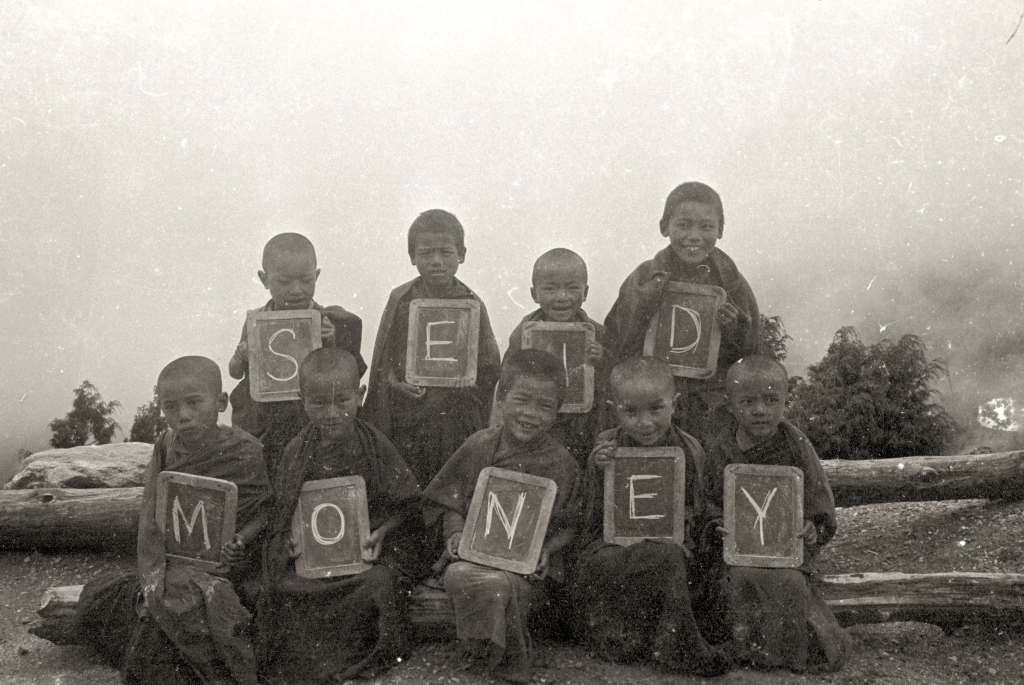

Around this time, Lama Lhundrup suggested that I think about raising funds to support the Mt. Everest Centre. I don’t remember how successful it was, but I did come up with the perfect picture to launch what turned out to be the first of fifty years’ fundraising campaigns!

September saw us continuing to do our respective things. Dick and Merideth’s blossoming romance annoyed me. While Marie and I were trying to get apart, they were trying to get together. Very self-righteously, I told Dick one day, “The purpose is to make progress; you’re going backwards.” He didn’t like that; nor did Merideth! But, to my mind, they were having sex all over the place up and down the hill and the fundamentalist in me hated it. Perhaps at some level I was jealous, but I really didn’t experience it as that. In fact, from the time Marie and I got to Kopan, our sexual desire, never that great to start with, completely dissipated. After the third course, when we moved back to Max’s Rana house, we slept in the same bed but had no interest in touching each other. It was completely natural, effortless and OK. Following the course, neither of us had any sexual desire.

One night at Lawudo we were lying next to each other in our sleeping bags and something in me stirred, some faint memory of what once was, and I reached across to run my hand over her. She recoiled in surprise, “Nicky!” I immediately pulled back, but felt fine about it, thinking yes, she’s right; we don’t need to do that anymore. So, we were in a very different space from Dick and Merideth and I was unfortunately extremely puritanical in my attitude toward them. That didn’t stop them, of course, and they later got married.

Tengboche

In October, a couple of weeks before we were due to return to Kathmandu, we heard that Trulshik Rinpoche was going to be at Kunde and Khumjung, a couple of villages up above Namche, just over the mountain from Lawudo. Gareth, Marie and I planned to go, but when the day came, I found myself bedridden by a sudden attack of prolapsed hemorrhoids. It was really painful; there was no way I could walk. I’d have to give it a miss. Marie and Gareth went off for a couple of days while I stayed home, nursing my thrombosed ’roid.

A couple of weeks later, however, I had fully recovered and as it was approaching the time for us to return to Kathmandu, I wanted to do something else while I was up there and get off by myself for a while, so I decided to take a walk up to Tengboche.

Credit: Neils David Williams

I made myself a big fat pak (tsampa dough ball) full of chura (rough-ground, powdered hard cheese) and set off. It took me about three hours to get to Namche, not bad time for an Inji, and after lunch I continued on to Tengboche, where I’d stay for the night and then next day go back to Lawudo. It was a beautiful walk and I felt great being off by myself. The mountains were beautiful, the trees were beautiful, the streams were beautiful; everything was beautiful. As I made my way up the final steep path to the monastery, I suddenly realized that I had nothing to offer the lama. Uncontrollably, my mind went to my signet ring. “Offer him that,” it said. “No way,” another part of my mind replied.

I had inherited this signet ring from my father. It was gold and had this amazing feature: inlaid in the flat part of the ring in a slightly lighter shade of gold was a swastika. This had always puzzled me a little that a Jew who had lost relatives in the Holocaust would be wearing a swastika, but since discovering the Dharma I had learned that it was actually an ancient religious symbol used by both Hindus and Buddhists, not to mention many other cultures all over the world. I doubt my father knew that, but it obviously did not just mean Nazis. For whatever reason, I was quite attached to this ring and didn’t want to give it up. My Dharma mind kicked in again: “If you’re attached to it, that’s all the more reason to renounce it. There’s much more merit in offering it to the lama than in wearing it with attachment.” I debated with myself back and forth all the way up the hill. By the time I reached the top, I had decided to give this man I’d never met my father’s ring, which I had inherited upon his death and not taken off for the past fifteen years.

I arrived at the monastery and looked around while waiting to see the lama. Finally, it was time, so I pulled out my khatag and went in, made three prostrations and offered him the ring along with the white scarf. He picked up the ring and looked at it curiously, as if he was puzzled that a complete stranger would give him this obviously valuable thing. He tried to give it back to me but I insisted he keep it, so he did. As I left the room, I felt a little odd at what I’d done and a pang of regret, but for some strange reason, the bigger part of my mind felt lighter, as if again I had actually practiced a little Dharma.

I stayed the night at Tengboche and the next day went back to Lawudo.

Denouement

I’d been back a couple of days when, much to my surprise, Lama reappeared, accompanied by Jampa Chökyi, who was planning to stay for the winter, and a Dutch painter, Wim, who’d painted some murals at Tushita and the wrathful figure on the doors of the Kopan gompa. Lama had come to check on the young monks, help close up the gompa for the winter and organize the monks’ move back to Kopan.

We got back to Kopan around the twenty-fifth of October, about three weeks before the fifth course was due to start…

This was a very good read at the end a very bad day. Thank you all @ LYWA

LikeLike

Thank you for this story, Nick. I continue to enjoy reading these and always find teachings in your words and experience.

LikeLike

Wonderful and inspiring story. Thank you Nick xx FPMT in Australia

LikeLike