by Nicholas Ribush

First published in the Love Lawudo Newsletter

The story of my first trip, 1973, finished with “We got back to Kopan around the twenty-fifth of October, about three weeks before the fifth course was due to start.”

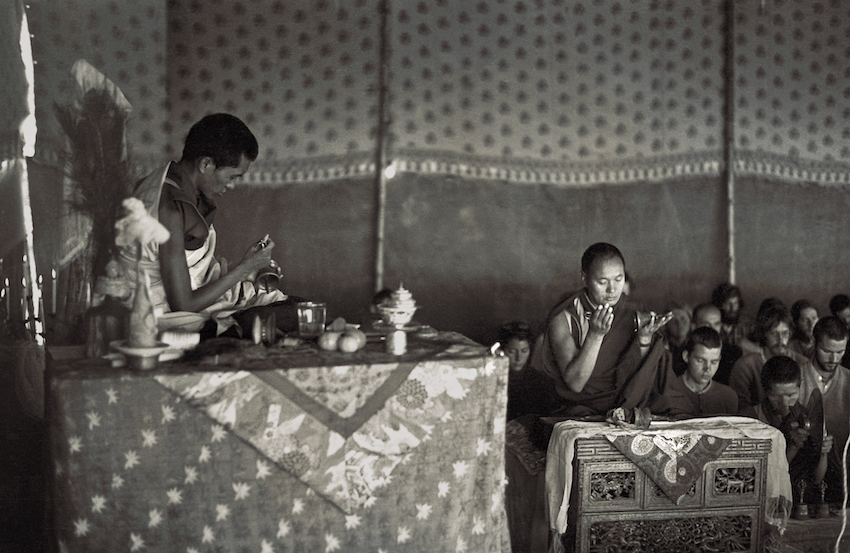

A lot of amazing stuff happened between my first and second trips to Lawudo, the winter of 1973–74. We typed the stencils of the teachings from the third and fourth courses that I’d edited in Lawudo so that we could mimeograph them in town. We built a kind of tent in the back yard to accommodate the two hundred students coming for the fifth course, since that many people would not fit into the gompa. When the course started I sat myself down right in front of Rinpoche and tried to write down every word he said, since when editing his teachings I had realized we missed a lot just by taking notes, and we had neither electricity nor a tape recorder. By the end of the course Lama Yeshe had given ten Western students, including me, permission to be ordained as monks and nuns, and on 15 December, 1973, established the International Mahayana Institute (IMI) as the FPMT’s monastic organization.

Lama appointed me as its first director. Practically all of Kopan then went to Bodhgaya, India, for the Kalachakra initiation to be given by His Holiness the Dalai Lama, after which we Injis, along with Rinpoche’s mother, were to be ordained by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche. We came back to Nepal and, in the old astrologer’s house in back of Kopan, established probably the first Western Tibetan monastic community. Lama gave us teachings on the tantric vows, which most of us had just taken for the first time. Then we prepared for and ran the sixth course, which was blessed for a week or so by the presence of Kyabje Zong Rinpoche. After that, Lama Yeshe and Lama Zopa Rinpoche started getting ready to make their first trip to the West, which was to follow a quick trip to Lawudo, but in the meantime, a couple of weeks after the sixth course, Lama gave about twenty-five of us the Heruka Vajrasattva initiation and commentary so that we could all do a three-month purification retreat while he was in the West, some of us individually at Lawudo, others in a group at Kopan.

All this meant Yeshe Khadro and I were pretty busy. I was planning to go to Lawudo to do my Vajrasattva retreat in the Charok cave. She was going to do hers at Kopan as quickly as she could and then go to Australia to help prepare for the Lamas’ visit. I was a little torn. Part of me really wanted to do the retreat, but I also didn’t want to miss out on the excitement of the Lamas’ first visit to Australia, which I felt I had been instrumental in bringing about. It was mostly my friends, people who’d come to Kopan at my behest over the past year, who were organizing the visit and my big ego wanted to share the limelight. But that wasn’t going to happen, and anyway, I had my hands full trying to get the transcript of the sixth course done.

Rudimentary electricity had finally been introduced at Kopan and we’d managed to get our hands on a couple of those old Panasonic push-button tape recorders. The taping had gone OK, but there were several power outages and we didn’t have decent batteries, so I planned to rely fully on the transcript of Sally Barraud’s shorthand.

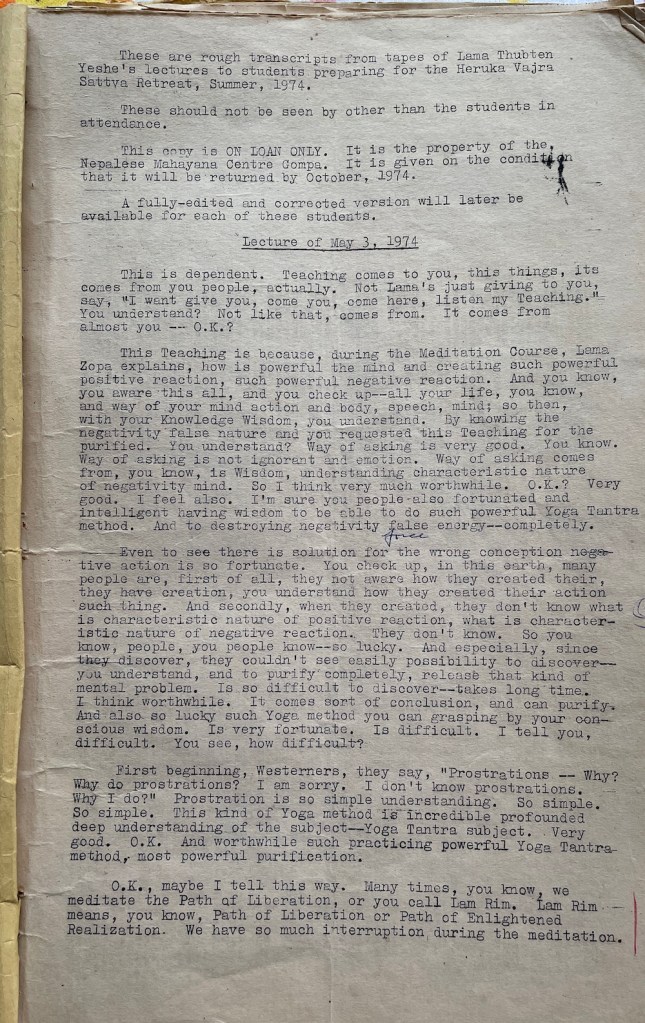

On 3 May Lama started his Vajrasattva commentary. It was wonderful teaching, which I later edited for publication by Wisdom as The Tantric Path of Purification, now titled Becoming Vajrasattva. We taped all six discourses and transcribed them as we went. There wasn’t time to edit them, so we finished up printing an unedited transcript for that summer’s retreaters to use.

This time I went to Lawudo on my own. I had many things to attend to in Kathmandu and was one of the last to go up. It wasn’t as much fun as it had been with the Lamas the previous year, but my stuff and I got there without any hassle. The plane even went the first day it was supposed to. Again, there was a wonderful nyung-nä with the Thamo nuns and some last-minute advice from Lama for those at Lawudo for retreat.

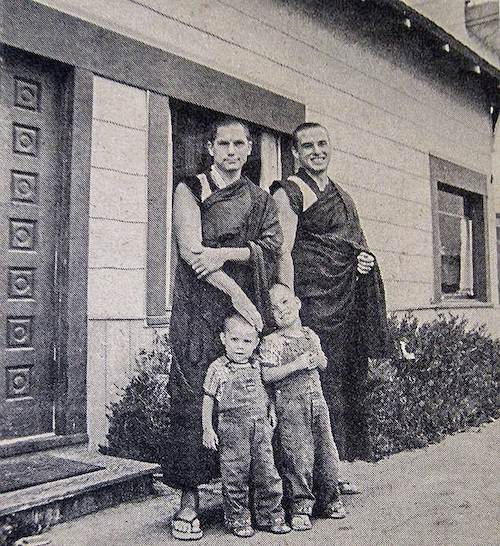

There were three women at the Genupa house—the nuns Ursula and Chökyi, and Bonnie Rothenberg, a woman from New York, who’d been at the fifth and sixth courses. Pende was in a house down at the Thamo nunnery. Chötak was in the little cave above mine at Charok. Harvey Horrocks, who’d returned from Australia to do the course, and Peter Kedge were in a small house at Mende. Wongmo and Nicole were in the gompa of a Phaplu house belonging to some people Lama Yeshe knew. Lama Lhundrup, Lama Pasang and the boys were, of course, at the Lawudo gompa. Since her ordination with us in Bodhgaya, Rinpoche’s mother was now living there, having moved up from her house at Thangme. All us Injis were there for Vajrasattva retreat.

The main event while the Lamas were there was the enthronement of another of the Kopan rinpoches, Charok Lama Tenzin Dorje. (In 1973 it had been Tenzin Norbu, Thubten Zopa “Small”.)

There was also a big puja out in front of the gompa, and the young monks were also put to work on some building projects.

A bit later in the summer all the Lawudo monks would go to Namche Bazaar for the annual July 6 celebration of His Holiness the Dalai Lama’s birthday.

Before the Lamas left, I asked Rinpoche if I could see him. At Lawudo, Rinpoche always stayed in his cave. It was amazing to see him there. I loved it. He seemed to grow in size and was visibly radiant.

I told him that I had been thinking about the teachings on guru devotion and it seemed that establishing a proper guru-disciple Dharma connection entailed some kind of agreement between teacher and student to enter into such a relationship. The teachings also emphasized the importance of the student’s checking a potential guru very carefully before making the kind of commitment that such a relationship demanded. I told Rinpoche that I hadn’t needed to check much, that it was his teachings and example that had clearly put me on the path and that therefore he was my root guru and, as unworthy as I was, would he please accept me as a disciple? Rinpoche thought for a moment and then said slowly, “Well, let’s try. I’ll try from my side and you try from yours.” And that was it. The pact was made.

One morning, Bruno LeGuevel, a French student who’d done the past couple of courses, arrived.

He had missed the Vajrasattva initiation at Kopan but desperately wanted to do the retreat and please would Lama give him the initiation? The Lamas were leaving that afternoon, so there was no time, but Lama said, “OK, at five o’clock this evening, you sit and meditate and think of me and I’ll give you the initiation from afar.” And that’s how Bruno got the Vajrasattva initiation. He wasn’t that well equipped and hadn’t organized a place to stay, so he didn’t last the summer.

I’d been spending a bit of time at Charok, fixing up the cave. It was a wonderful cave, practically five-star.

It was one of those made by building up walls around an overhanging rock that had plunged from far above and half-buried itself into the face of the mountain. It had a wooden floor, windows, which I covered with polythene, and a door, a mud and stone stove and two rooms. The inner room was separated from the main one by a wooden partition that reached three-quarters of the way up to the sloping, slightly damp undersurface of the rock, which formed my ceiling. In the inner room was a meditation box. A meditation box was a low platform about four feet square and stood about two feet off the floor. It had wooden sides like a little fence around it, higher at the back so that you could lean back a little into it. Inside you put your meditation cushion and in front of it stood a small table on which you kept your text, dorje, bell and damaru, inner offering and whatever else you needed to get your hands on during a session. It stood with its back to the front wall.

There was a rock ledge on the wall opposite the box, upon which I made my altar. On the other side of the partition I laid down my mat and sleeping bag. I had brought four months’ staples with me from Kathmandu and also bought some food locally. I had rice, potatoes, tsampa, yak butter, a couple of types of hard cheese, powdered milk, flour and sugar. I had also arranged for Tsultrim Dolma, a nun from Thamo whose brother, Tsultrim Gyaltsen, was a monk at Kopan, to shop for me once every two weeks at the Namche market Saturday mornings. I planned not to talk to anyone for the entire retreat period, so before I started I gave her a note with what I wanted the next Saturday, and each fortnight after that she would get my stuff, leave it outside the cave and pick up the note I’d left with the next fortnight’s list. She’d bring whatever green vegetables she could get—which wasn’t much, got less as the summer went on and would last only four or five days—a kind of cream cheese they made up there, which also wouldn’t last the fortnight, and whatever other things I needed, like matches, candles and so forth.

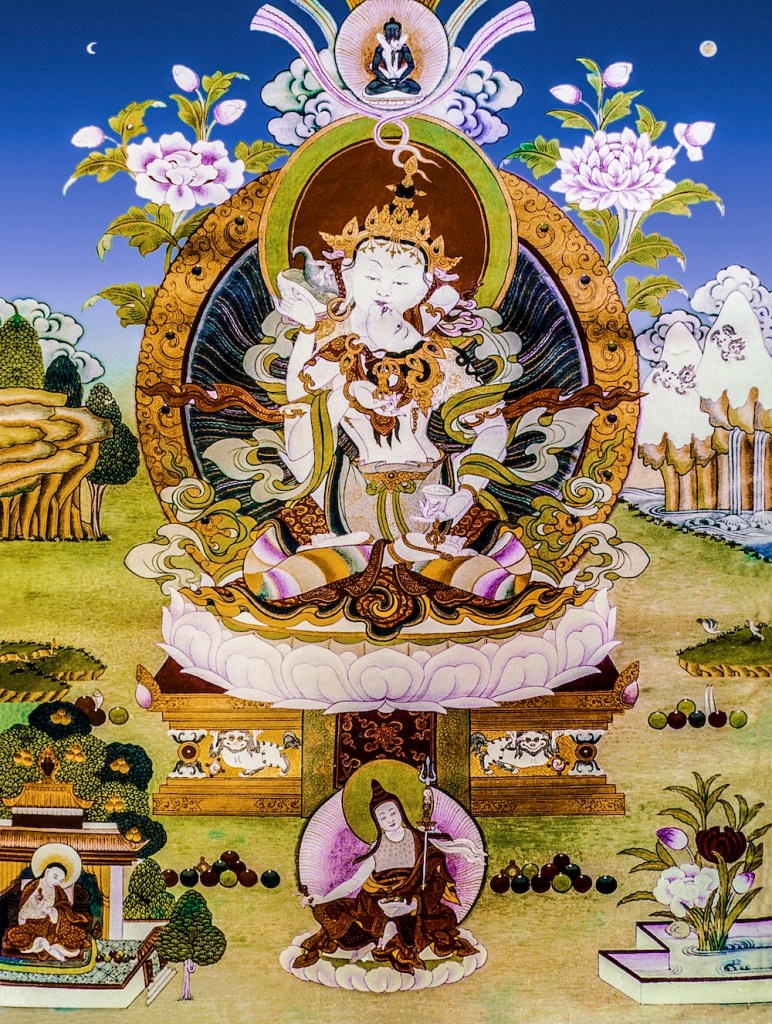

The Lamas left and, following Lama’s instructions, I started retreat. Lama had put together a sadhana, or method of accomplishment, that was based on the Vajrasattva practice in the long sadhana of Chakrasamvara, Lama’s principal deity. The idea was to do the sadhana four times a day and during the retreat, recite the Vajrasattva mantra 100,000 times, plus ten percent to make up for errors in recitation. I figured it would take me the best part of three months.

If the best possible place in the universe to be is at Lawudo for nyung-nä at Saka Dawa with the Lawudo Lama and the Thamo nuns, retreat in the Charok cave at any time of the year must come in a close second.

In front of the cave was a tiny walled-in yard, below which the mountain dropped sharply away. You entered the yard through a small arched gateway that was just to your left as you exited the cave door. Looking straight ahead, you saw the high, snow-capped mountains on the other side of the valley. Way below, out of sight from here, were the swirling waters of the Dudh Kosi. Everywhere around were the most beautiful wild flowers, and the Genupa house lay about a ten-minute walk below. Every two weeks there’d be a new crop of flowers and I was so happy to offer beautiful bunches on my altar every day.

Starting the fire was always a bit of a problem, so one of the first things I did after getting to the cave was to collect as much juniper as I could and stash it in a dry crevice under the rock to the side of the cave and hope it would stay dry enough to light throughout the summer, when the climate was damp and my part of the mountain was shrouded in mist for half the day.

Damp notwithstanding, water was also in short supply. I had to get mine from a small stream about twenty minutes up the mountain from where I was, near a place where, a couple of years earlier, Ngawang Khedrub (Ron Brooks) and Ngawang Chötak (Chris Kolb), before either of them was a Ngawang, had built a native American sweat lodge-cum sauna and nearly gotten third-degree burns through injudicious application of cold water to overheated rock. I had a large biscuit tin that just fit in my backpack, and every three or four days I’d march up the mountain to the spring, which during the summer receded further and further up the mountain until by the end it was barely more than a trickle, fill the tin and gingerly carry it back down, trying not to spill a drop to both conserve the water and prevent that nasty feeling of cold liquid trickling down the back of your neck when you’ve got perhaps eighty pounds of the stuff strapped to it. Nevertheless, Lawudo was, and remains, an ideal place for retreat.

Lama recommended starting retreat gradually, the length of the sessions following the shape of a barley grain, which is pointed at each end and wide in the middle. That means you start with many short sessions a day, gradually increase their length and decrease their frequency until you get to the desired four two-hour sessions a day. I started with six one-hour sessions a day for the first week while I accustoming myself to the sadhana, studying Lama’s commentary and getting used to the situation in general. Furthermore, I decided to take the eight Mahayana precepts every day to squeeze every drop of merit out of the experience, which also meant I’d have to make a fire only once a day.

I’d brought a big Chinese vacuum flask with me. After my second morning session, which finished about 10:30, I’d light the fire, which could take anything from ten to thirty minutes, depending on how wet the juniper was. It did get drier as the summer wore on. Once the fire was burning, I’d boil a big pot of water and make black tea, with which I’d fill the flask, and use whatever water was left to make lunch. I’d usually make enough food to last three or four days so that on the other days all I’d have to do was heat it up. This would be my famous Lawudo stew, renowned the length and breadth of the Charok cave, containing potatoes, tsampa, squares of hard cheese, which softened over the days, and any greens that I might have. After a couple of months, the nettles came in and for the next six weeks or so I had fresh greens every day. They were stinging nettles, tricky to pick, but once they were boiled it was like eating spinach. I’d learned about nettles the summer before, because they grew like crazy around the Genupa spring. Eating nettles always made me think of the great yogi Milarepa, who was said to have turned green from subsisting on nettles for years and supposedly had a retreat cave not far from Charok. There was an old, broken-down cave nearby that we used to speculate might have been the one, but I never found out for sure.

I’d have a cup of tea around five in the afternoon and then nothing more before going to bed, which I did around ten. I found that timing it like this I’d have to get up for a pee around the time I wanted to get up anyway, so in that way my bladder became my alarm clock.

You were supposed to finish your first morning session before sunrise. That meant arising around 3:30, because it took me about half an hour to wash, set up my altar for the day and do all my morning prayers and take precepts before starting the actual session. Actually, I don’t know why I mention the wash, as it was somewhat perfunctory. I just cleaned my teeth and splashed a little cold water on my face and hands. Even though it was summer, it was fairly cold and damp most of the time. I didn’t completely undress to go to bed, just took off my shemthab and dongka, leaving on my socks, slip and undershirt. It was six weeks before I took my socks off for the first time. That was pretty interesting!

Sunrise was around six. Since I’d taken precepts, all I had for breakfast was what was left of the tea in the vacuum flask, which was still acceptably warm. Once I’d gotten into this routine, I decided to lengthen my sessions by half an hour so that I was meditating ten hours a day. As the retreat progressed, I found that I needed less sleep; four or five hours was plenty, a great discovery, since my mother had brought me up to believe that I’d die if I didn’t get my full nine hours. During the breaks I read some of the books I’d brought with me or studied Lama’s commentary.

When Lama taught, he’d often mention by name this person or that in the audience, sometimes making jokes at their expense, sometimes using them to illustrate a point. When Lama gave us the Vajrasattva commentary, he mentioned me a few times in various ways. I started examining the context of these mentions as well as looking in depth at other teachings Lama had given. Suddenly I realized that in these teachings, Lama had been sending me subliminal messages. I was going to die in this retreat. No way! If Lama had known my number was up, he wouldn’t have sent me up into the mountains, where there’s no hope of medical attention. Or would he? Perhaps he could see that whatever it was that was going to kill me couldn’t be stopped and that the best thing for me was to die in purification retreat. I still couldn’t believe it. I was perfectly healthy; I’d hardly been sick a day in my life, apart from the previous year’s bout of hep, from which I’d completely recovered. How could I be going to die?

I examined the teachings again. Here was a part where Lama was saying that we should do retreat without expectations. We should think, “I don’t care whether or not I get any realizations. The only decision I should make is to act as positively as possible from now until I’m dead.” Now, everybody knows that this is a standard teaching, but I took it personally. I looked further. Here was a bit where Lama said, “No matter where you go, even behind a locked door, you can’t escape your karma. Whether you are near people or not, karmic reactions come automatically.” If karmically I had to die, it didn’t matter where I was.

Now I read the part where Lama was criticizing those students who knew the words but didn’t practice. They could spout this teaching or that, but when it came to the crunch they were lost because they hadn’t actualized the meaning of the words. That was me. I’d spent all this time working on Rinpoche’s teachings. I knew the words, but in my heart, I knew my practice was nothing. I was hung up on the intellectual, just as Lama said. I needed to get some solid practice under my belt. That was why I had to be in retreat when death came, just like Zina had been the year before. Lama had known she was going to die and had put her in retreat—at least that was my theory. This year it was my turn.

Lama went on to say, “Some students here just want to learn to talk about Dharma so that they can tell their mother and their friends.” That was me again. I’d had my mother and friends come to the fourth Kopan course last year. “Such people,” Lama continued, “When serious problems arise within them, they have no solution. They can’t put the words they know into action because they’ve never practiced. This is very dangerous” “Serious problem,” I read; “Very dangerous.” Death’s a serious problem; death’s dangerous. That’s me—the intellectual who won’t be able to handle death. I was sure Lama was talking to me in all of this and he hadn’t even mentioned my name yet.

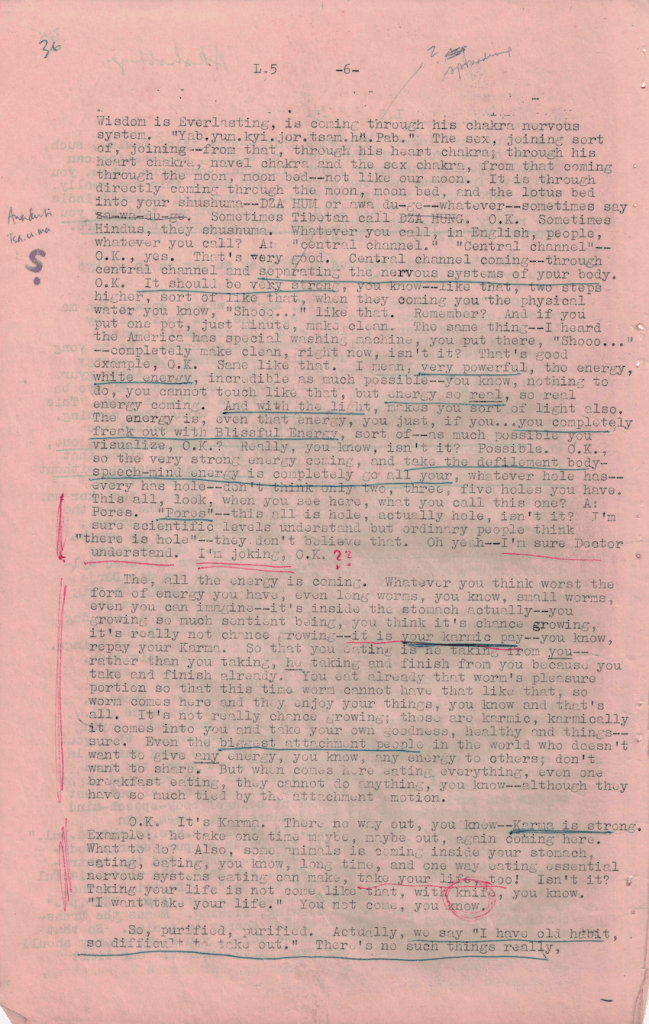

“Look at Kopan,” Lama was saying. “It’s supposed to be a peaceful place but everyone there’s always so busy, busy, busy. For sure, life finishes soon, that’s all.” I was one of the busiest people at Kopan. Surely this meant me. Now came the bit about the worms. Lama was explaining one of the purifying visualization techniques, where you visualize all your negativities coming out of your pores. “People look at the skin and can’t imagine that it’s full of holes, but scientists know. I’m sure Doctor understands,” Lama added, looking at me. Now he had my attention. He went on. “Visualize all your negativities coming out in the form of the worst energy you can imagine, such as worms. Long worms; short worms.” My paranoia and hypochondria kicked into high gear. This had to be me. I’d just recovered from a serious worm infestation that I’d picked up in Bodhgaya a few months earlier. “Worms don’t come into your stomach by chance,” Lama said. “It’s your karmic payback. In the past, you took from the worms; now they have come to take back from you. Karma is strong. Even if you get rid of them, they come back. They can eat your entire nervous system and take your life. Having your life taken doesn’t necessarily mean someone attacking you with a knife.”

That was it! Now I knew I was done for. “We have such a short time to purify. You waste your time eating, talking, going here and there, and without having time to practice, whoosh! Your life is over.” Everything I read in this commentary was telling me I was going to die up here. “Dogs’ minds are up and down a hundred times a day. They have no idea how to develop their minds. We’re the same. While our minds are preoccupied by the illusory fantasies of our ego, life finishes.”

What could I do? Now I was stewing over this and not getting much meditation done. I should put these ideas out of my mind and get down to the serious business of purification, which is what I was there for. I tried, but I was obsessed by the idea I was going to die. I even wrote on the cover of my commentary, “Materials for an Obituary.” It’s there to this day, with all the above death quotes underlined in red. This was my ego at work. I figured that if I was found stiff in the cave, when they looked at what I’d written, people would nod wisely and say, “Look at this—he knew he was going to die,” and be filled with admiration for my devotion to practice. Even if I was dead, my eight worldly dharmas would be alive and well.

But I couldn’t stand it any longer. I took a walk over to the gompa to consult Lama Lhundrup. “Gen,” I asked him. “Did Lama arrange with you to have any pujas done for me up here in the case of my death?” A perplexed look crossed his face for a moment while he processed what I’d said to make sure he’d understood. Then he suddenly clapped his hands delightedly, threw back his head and let out a loud, high-pitched laugh. “That’s good,” he said. “That’s very good.”

“What’s good?” I asked. “That I’m going to die and you’re ready to go with a big puja for the dead?” “Lama not say to me puja,” Lama Lhundrup replied. “You, good understanding. That right. You very lucky. You good understand lamrim.”

I gathered from all that that at least, Lama had not told him I was going to die. All Lama Lhundrup could say was that he was happy that I seemed to have some feeling for the teachings on impermanence and death, especially those that death is certain, its time is most uncertain and that the only thing that can help at the time of death is Dharma.

Here was another thing that had impressed me about Buddhism. No topic was taboo; everything could and should be thought about, studied, analyzed and discussed. I was a doctor. I’d been around death for fifteen years, starting from dissecting corpses in the anatomy room to certifying dead patients in the hospital ward to poking around cadavers at autopsy. Surrounded by death in those ways, I had never really thought about it, never really considered my own death, never looked at those bodies and thought, “One day, that will be me. There’s my destiny, right there.”

This seemed to be the Western way, from defecation to old age to death. Out of sight, out of mind. It brought to mind the teachings on the god realms, celestial planes of existence more refined than our human realm but still within cyclic existence, still suffering by nature. There, when gods were dying, their beautiful bodies would lose their radiance, their flower garlands would wither and die, their bodies would start to stink and their friends would shun them and turn away, leaving them to die alone. This sounded to me a lot like the way we treated old people in the West, and it had been a revelation to me to see how much closer families appeared to be in traditional societies, like those I’d seen in Asia. But, dying old people bring us down, so let’s put them away somewhere and pretend they don’t exist. Our attitude to death was similar.

We made the idea bearable by pretending that there was a nice place called heaven, where most people went unless they were people we didn’t like or approve of, in which case they went to this other place called hell. We also couldn’t do that much about the time of our demise, so we pretended that it was all up to God. With those considerations out of our hands and out of the way, we forgot about death and lived our lives as if they’d never end, and if anyone wanted to talk or think about human mortality, we didn’t want to know.

Buddhism wasn’t like that. You could speak about or look at anything. Lama used to say that you can call the Buddha a pig, as long as you can back that statement up with logic. And, as with everything else, the Buddhist approach to death was clinical, scientific and based on experience.

Lama Lhundrup was telling me that the way I’d been thinking was good. How was it good? I was about to find out. I went back to the cave feeling slightly reassured but a little disappointed at how easily I could work myself up into a hysterical frenzy. In a calmer frame of mind, I thought it all through again. No, Lama wasn’t saying directly, “Dr. Nick, goodbye. We’ll never see you again.” When I looked dispassionately at the transcript, Lama was talking in generalities. Nevertheless, when I applied what he was saying to me, there was nothing to say it wasn’t true, that it couldn’t happen.

Sometimes I wondered if Lama had known Zina was going to die and had still let her go up to a remote place for retreat, in the scheme of things that being the best thing to do. That could also apply to me. Lama was saying that when starting retreat, don’t expect anything to happen, simply resolve, “From now until I die, I’ll do my best.” Nothing personal in that; many lamas taught the same thing. Lama also said that we cannot escape our karma; that, too, is a fact. Where Lama talked about things in general and I applied them to myself, even the bit about the worms, that was good; that was exactly how you were supposed to listen to Dharma teachings—to use them as a mirror for your own mind. That’s also what Lama Lhundrup was implying.

I concluded that I didn’t have a clue what was going to happen over the next four months and that instead of driving myself nuts through speculation, I should focus on the task at hand—as thorough a purification of my mind as I could possibly manage—and allow nothing extraneous to enter it. After all, was there one person in the entire world who could say with conviction, “I’m not going to die today”?

Now I was able to use fear of death to my advantage. Whenever I noticed my mind start to wander, I would immediately think, “Hey! You’re going to be dead soon, don’t worry about that.” It worked; it worked really well. And even though my visualization was still extremely poor, I was able to control the gross scattering of mind that had always characterized my attempts at meditation up until that point.

I got into the retreat, but after about a month I took stock of my progress. It was pretty dismal, especially my ability to visualize the deity, Vajrasattva. The image I was using was a photograph I’d bought from Das Photo in Kathmandu, a thangka painted by a Westerner that Rinpoche had once told me was his favorite image of Vajrasattva. I’d counted about 25,000 mantras but felt that because my visualization was so poor, I probably hadn’t purified much. Also, Lama had given very strict instructions as to what constituted a valid mantra count and what the disqualifications were, and I also felt I had not lived up to those.[1] I figured it was better to start over, so I did. I went back to the beginning and started counting from 1. A month later, I took stock once more. Another 30,000 mantras but still not much of a visualization. Maybe this was me. Perhaps, for me, this was as good as it got. I hadn’t achieved anything by starting over. Stuff that; I’d include the first 25,000. My tally was now 55,000 after all.

Now that the pressure was off, I relaxed. Lo and behold, I started to be able to visualize a bit. Not much, but there was a little light and the occasional detail. And I was still able to control distractions by thinking about death. As time passed, I started wondering about the Lamas’ trip to Australia, which must have been coming up around that time. Lama had prepared me for that—when explaining in great detail which mantras could be counted towards the total and which could not, he had said, “If, while you’re reciting mantras, your mind goes into a New York supermarket, you’ve broken your concentration; you can’t count those. You have to return to the first bead of your mala and start again. This is the worst thing. You can’t allow your mind to wander. While in retreat, you’re also not allowed to go to Diamond Valley, in Australia.” This was the valley next to Tom and Kathy’s farm, where the Lamas’ first Australian lamrim course was to be held. Lama knew I’d be thinking about it in retreat and, in fact, I often did find my mind wanting to go there. But I could always bring it back by remembering that I wasn’t getting out of these mountains alive.

Anyway, if I’d followed Lama’s instructions literally, I’d never have finished even one mala, so I decided to try to take them seriously, but to follow them more in spirit than to the letter and just do the best I could. This seemed to work. My distractions decreased and my visualization improved some, but the main thing I learned was that I was, as Lama would say, “Long way baby.” Somewhere Lama had seen the well-known TV advertisement for Virginia Slims cigarettes, which quoted a line from the song You Came a Long Way from St. Louis: “You came a long way from St. Louis, but baby, you still got a long way to go!” (See Big Love, p. 265.) In fact, Lama had used this idea to help me a year or so previously when I was feeling a bit hopeless and he told me to look way into the distance and think, “I’ve come a long way.” But in general, when Lama would say, “Long way baby,” I think he was referring to the punch line, “You still got a long way to go.”

In the third month of my retreat, around the 80,000 mark, I was into my first session of the day, reciting away, when I felt this strange sensation in my pelvis, like I was having an orgasm, but deeper. I lifted my shemthab and glanced down into my lap. It was perfectly dry. I went back to my recitation. Not only did the feeling persist; it got stronger. My concentration improved; nothing could distract me. Mantras flew effortlessly off my tongue. The blissful feeling increased. An hour passed. Now it was time to wind up the session. Lama had told us many times that the best time to finish a session was on time, when you were feeling like you could keep going. Lama said that even if you felt like continuing, you should stop; it was a mistake to keep reciting mantras until you were exhausted. If you did that, you’d start to develop aversion to your meditation cushion and feel sick whenever you saw it. But I was in the zone and there was no way I could stop.

Another hour passed. My concentration remained firm, the bliss continued and the mantras kept coming. After yet another hour, even though I still felt like continuing, I’d taken precepts and had to stop for lunch. I’d done both morning sessions in one. Now I had an idea what all the fuss about meditation was. Perhaps I’d had some kind of breakthrough and from now on it would always be like this. That would have been pretty far out.

At the same time, I felt incredible devotion to the Lamas and the deity, Vajrasattva. After dedicating the merits of the session, I got up and the first thing I did, before making lunch, was to make a huge tsampa torma and, with tears of gratitude pouring down my cheeks, offer it to the guru-deity. Then I had lunch, eagerly looking forward to the next session, which I was determined not to start early and to finish on time, no matter what happened.

When I got to the mantra recitation in the next session, I still had some blissful feeling in my lower chakras but it was much weaker than before. By the evening session, I was back to normal. I’ve never had another experience like that but I’m sure I’ve been coasting on that energy ever since.

Later, when I told Lama about this experience, he said simply, “Wah, Dorje Sempa [Vajrasattva] really blessed you.” Having seen the admonition that you’re supposed to keep your realizations secret lest they lose power, I’ve never told anybody else about this until now, but since this was a one-off occurrence and didn’t last and is therefore not a realization, there it is!

By the time October came I’d spent four and a half months in the cave, recited about 120,000 mantras and didn’t want to leave. I could have stayed there for the rest of my life. I loved the cave, I loved the place and I loved the practice. But duty called. Lama intended for Anila Ann to remain in Australia to develop and teach at Chenrezig Institute and had asked me to fill in for her and assist Lama Zopa Rinpoche at the seventh course, which was due to start November 6.

Accordingly, around the middle of October, I dedicated the merit of the retreat to the long and healthy lives of all my gurus, especially Lama Yeshe and Lama Zopa Rinpoche, the spread of the holy Dharma infinitely throughout the ten directions and the immediate enlightenment of all mother sentient beings, packed up my stuff, bade farewell to all at Lawudo and set off towards Lukla. As I trotted down the mountain I realized I hadn’t died and felt the sort of relief those guys on death row must feel when they’re exonerated by a DNA test and set free.

I got back to Kopan without incident and started preparing for the course. After the debacle of the sixth, for which two-hundred-and-fifty people had enrolled and was far too many for Kopan to handle, resulting in about seventy of them leaving for various reasons, we had a new plan—the interview.

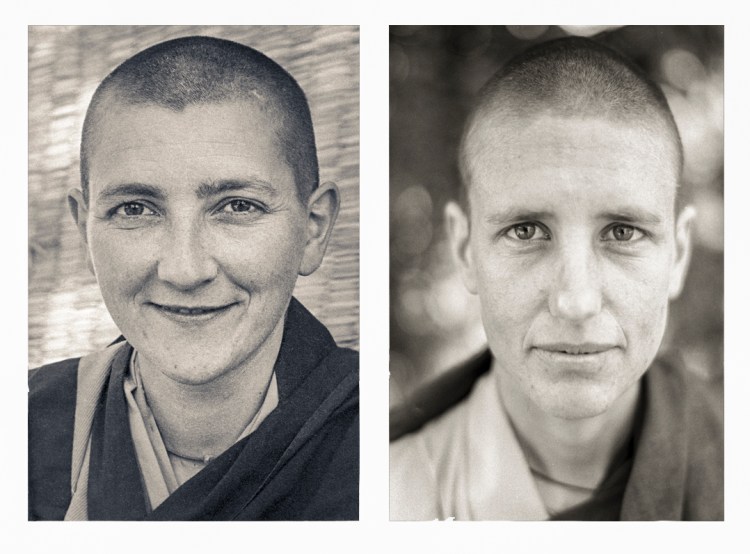

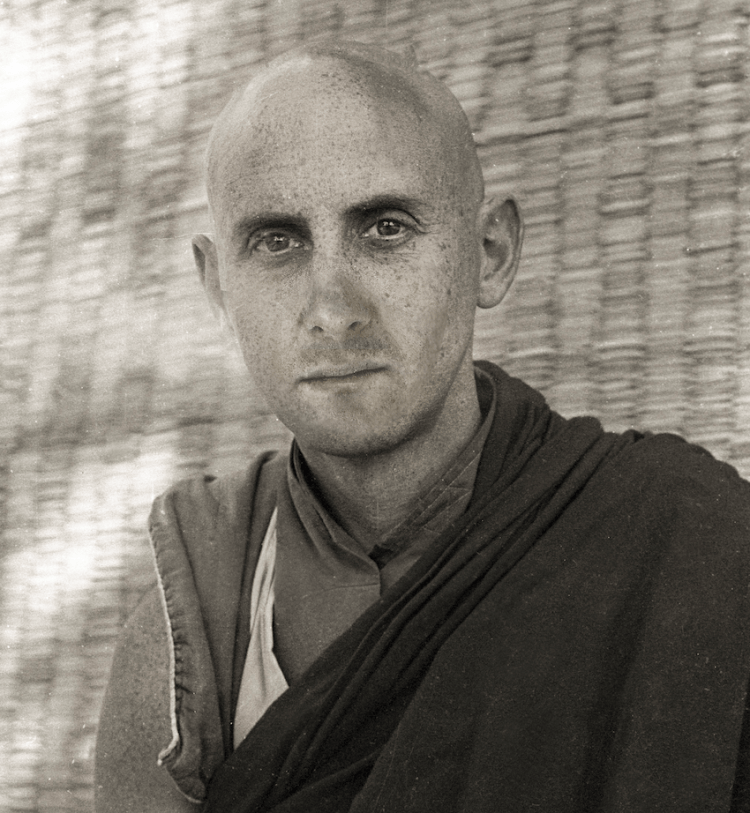

Up until now, all anybody who wanted to do the Kopan course had to do was show up, plonk down about three hundred rupees and they were in. In order to avoid the disruption of another mass exodus, we decided that we ought to warn people what they were getting into and even printed up a two-page sheet showing the daily schedule and all the disciplines they were supposed to follow. Two monks—Ngawang Chötak and Tubten Pende—were selected to do the actual interviewing. As monks, these guys cleaned up very nicely and looked a bit like those handsome young Mormon missionaries that used to go around in pairs converting the world—except for the shaved heads and maroon robes, of course.

So, anybody wanting to sign up for the Seventh Kopan Course had to go down to a little room in the old house to be vetted by Chötak and Pende, whose job wasn’t to decide who got in and who didn’t, like bouncers, but just to make it clear that the course was a serious thing and that people had to attend every session and follow the rules. I don’t know how many people actually decided against doing the course, but by the time it started a few weeks later, about two hundred people were there for the first session.

The Lamas arrived in India from Australia towards the end of October and went to Mussoorie for a short break. Rinpoche got back to Kopan in the first week of November while Lama stayed in India for a while longer.

To be continued…

[1] See Lama Yeshe’s Becoming Vajrasattva (Wisdom: 1994), Part 2: Retreat Instructions.

One thought on “My Second Trip to Lawudo, Summer 1974”